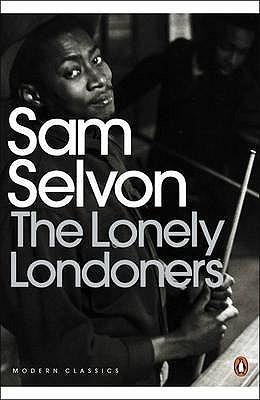

First published in 1956, Trinidadian born, Sam Selvon, began his London based fictions with a short novel called The Lonely Londoners. It’s set during a time when many West Indians were emigrating from a life of sunshine to the British Isles, believing, like many emigrants, that the streets were paved with gold. Of course, this is London we’re talking about; there’s no gold.

The book, for the most part follows the fortunes of Moses Aloetta, a Trinidadian who has lived in London for years, as his life meets tangentially with others. His time is spent between his job, in which he is paid a meagre wage, and heading on down to Waterloo to meet the latest influx of West Indians.

There are all manner of characters coming to London, and not only from the West Indies. Shiftless ladies’ man Cap, for example, is Nigerian. But the majority are coming from Trinidad and Jamaica. Local prejudice tends to label all the black immigrants as being Jamaican, which rankles Moses. Other characters include Henry Oliver (nicknamed Sir Galahad), a young kid looking to start over in London; Tolroy, who on writing home to say he gets paid five pounds a week, wasn’t intending the letter to be an invitation for his whole family to join him; Five Past Twelve, an ex-soldier always on the scrounge; Big City, who has always been captivated by urban living yet can’t quite integrate; and Harris, a man who has found himself in London yet is still tied to the burgeoning black community.

The novel follows their fortunes as they come to Moses for help, as they crash in on each others’ lives, and flirt with the white women who see them as a novelty; all the time wondering if they will ever return home. Through all this, though, there’s a sense of unease. For the native Londoners there are too many black people coming for work; the immigrants also share this resentment, in that the other immigrants are seen as competition for what little jobs are available. Most jobs, when the person is discovered to be black, tend to offer lower wages too.

What makes The Lonely Londoners special is the narrative. Rather than a straightforward English narrative, Selvon has opted for the third person narrator to tell the tale in creolised English, which give the effect of bringing the reader into the immigrant community:

When he get to Waterloo he hop off and went in the station, and right away in that big station he had a feeling of homesickness that he never felt in the nine-ten years he in this country. For the old Waterloo is a place of arrival and departure, is a place where you see people crying goodbye and kissing welcome, and he hardly have time to sit down on a bench before this feeling of nostalgia hit him and he was surprise.

Selvon’s characterisation works well with this creolised style but it’s more than a tragi-comedy of the life in fifties London as immigrants try to find work and settle. Life is hard, the people reduced to living in small rooms. Jobs are scarce. And there is much racism coming from the local people and businesses, which Galahad struggles to understand when, still hoping for a job, he says:

“The Pole who have that restaurant, he ain’t have no more right in this country than we. In fact we is British subjects, and he is a foreigner.”

Galahad takes this further when he addresses the colour Black itself:

Why the hell you can’t be blue, or red or green, if you can’t be white? You know is you that cause a lot of misery in the world. Is not me, you know, is you! I ain’t do anything to infuriate the people and them, is you! Look at you, you so black and innocent, and this time you causing misery all over the world.

The Loneley Londoners doesn’t follow a conventional storyline, opting instead to collect a bundle of stories about its characters adapting to life in London, using Moses as their backbone. This method actually gives the story more direction than one would expect and also blesses it, for its size, with an epic feel.

For all its sense of community, The Lonely Londoners, as you would expect from title, isn’t a bunch of laughs. Sure, there’s much comedy to be had, but an undercurrent of sadness runs throughout. Employment, racism, immigration, relationships, personal ambition, and nationality all come under Selvon’s spotlight in a book that is anything but black and white.

Beautiful! without holding back, I am compelled to say that this site has surely assisted me in understanding the effects of Selvon’s hybrid English Language in his novel. But do permit me to rely something that crossed my mind whilst reading this article. Selvon deliberately uses the hybrid language (which is both English and West Indian dialect) to synchronize with the Creole man-a west indian- living in London-an English speaking State.

Max drew my attention to this book and his review — and this one — convinced me to read it. I loved it and have left some extended thoughts on Pechorin’s Journal but wanted you to know your review was very much an influence.

First, here’s Max’s review on Pechorin’s Journal (now added to Blogroll).

Sad you won’t be writing about it, but happy you enjoyed it. I’ve just been tidying up my shelves this evening and looked at the sequel, Moses Ascending, remembering an intention to read it long ago. Then I put it back on the shelf again.

I plan to read Moses Ascending this year, I just wanted to leave some space between the two. I understand the tone is quite different.

Currently I’m still bogged down in Herodotus anyway. Bogged down implies Herodotus isn’t fun, it is in fact huge fun, it’s just not suitable for reading on the way to work and so I’m struggling to make progress. Ah well.