“Life, I do not understand you”, writes Doctor Tyko Gabriel Glas in his diary as events draw to a close in Hjalmar Söderberg’s classic eponymous novel, Doctor Glas (1905), and it sums up all of his frustrations at his understanding of the world around him and at the life shattering realisation that life has passed him by. Of course, if it has passed then it has been his own doing, and how things have come to be so make the reading of his diary a rich and rewarding experience, even if it breaches (albeit in reverse) the whole doctors and confidentiality thing.

Set in Stockholm over an unusually hot summer, the likes of which he has never known, the thirty-something Doctor Glas tends to his patients by day and scribbles away in his diary at night. The entries are wide ranging, covering his day to day duties, his encounters with people in his wider circle, and his deeper reflections on the nature of the world and of himself.

One of the first questions he asks himself is one of the more unusual ones:

How can it have come about that, out of all possible trades, I should have chosen the one which suits me least?

For a doctor, he has a strange understanding of life. He shuns something as natural as sex, disgusted by how filthy it sounds (“why must the life of our species be preserved and our longing stilled by means of an organ we use several times a day to drain impurities?”) and spurns any attention shown to him, despite admitting that “I’m alone and the moon is shining, and I long for a woman”. One women, it is mentioned, has even made her interest known, but he can’t remember her mouth, and “one is only really familiar with a mouth one has kissed, or longed very much to kiss.”

One such mouth, however, belongs to Helga, (“whose heart was full of desire and misery”), the young wife of the “loathsome” Reverend Gregorius. She comes to his surgery one day, not through illness, but to ask of him a favour, saying that she is tired of her husband taking his rights in the bedroom and could he please say that she has an infection of the womb in order to deter him, even admitting that she has another lover. Whatever efforts Glas makes, however, helps only temporarily and Gregorius returns to old ways, effectively raping his wife.

All other options exhausted, Doctor Glas wrestles in his mind over the notion of murder, wondering whether removing Gregorius from the picture is the right decision. “Morality, that’s others’ views of what is right,” he tells himself:

Morality becomes consciously for me what it is in practice for each and every person, although all do not recognise it: not a fixed law, binding above all, but a modus vivendi, useful for daily life in that unremitting state of war which exists between oneself and the world.

And so he takes to wandering around with a small number of cyanide pills he had originally fashioned for himself, back in the days when he had contemplated suicide. Indeed, if his plan were not to go well he realised he must still consider that option.

While the novel’s surface expertly handles a twisted love triangle, it is the novel’s attitudes to such themes as abortion, euthanasia, and women’s right’s that make it a particular stand out. For a novel written over a hundred years ago, its ideas are incredibly prescient:

The day will come, must come, when the right to die is recognised as far more important and inalienable a human right than the right to drop a voting ticket into a ballot box. And when that time is ripe, every incurable sick person – and every ‘criminal’ also – shall have the right to the doctor’s help, if he wishes to be set free.

What makes these themes more interesting, in light of the narrative, is that the presentation is never didactic. Glas doesn’t so much believe in women’s rights as act in his own interestes towards the reverend’s wife. He refuses the women who come to him begging abortions, as his duties don’t allow it, although he does sympathise, especially on coming face to face with the product of one such opportunity.

Söderberg has done a brilliant job of making Glas a man of contrasts, his suggestive name hinting at his transparency, no matter what he himself sees. At times a seemingly generous soul, willing to help, his psyche goes deeper, darker, and into selfish realms. And no matter how much he may deceive himself, he still provides an understanding of the world and people:

We want to be loved; failing that, admired; failing that, feared; failing that, hated and despised. At all costs we want to stir up some sort of feeling in others. Our soul abhors a vacuum. At all costs it longs for contact.

Coming to the conclusion of Doctor Glas, and longing for the winter after the summer, it’s no wonder that Glas does not understand life. Indeed, he writes, “Life is action, When I see something that makes me indignant, I want to intervene.” but he can do nothing to intervene in his own circumstances.

Remarkably modern, Doctor Glas provides a fantastic slice of the gothic in a narrative that is, by turns, invigorating and horrific, and told with such succinctness that begs the question of why many modern novels contain so much fluff. It’s dark, refreshing, and completely enjoyable; as fiction goes, it’s just what the doctor ordered.

I started reading this last year but found it hard to concentrate on it, which I know was my fault and not the book’s, as parts of it were nonetheless fascinating – I didn’t so much give up on it as put it on hold until I could do it justice. That time may now be upon us!

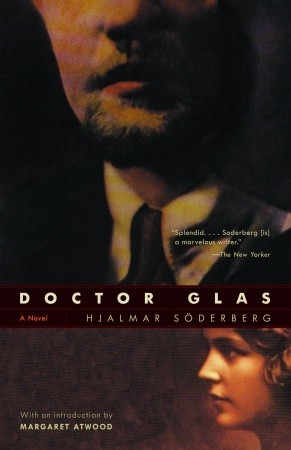

Is that the cover of your edition? Mine is a hardback Harvill (I reckon just before they became Harvill Secker). I didn’t know it was available in paperback – mind you, as my hardback was something like the third or fourth printing, it seemed to be doing pretty well for itself as it was.

Yes, the photo is the copy I have. It’s the US paperback edition from Anchor Books.

Yes, I have this somewhere! And, as I recall, it is a smallish Harvill hardback with — if memory serves — a glowing quote from Susan Sontag stamped on it … I’ll have to chase it down. Thanks for reminding me!

This one?

That’s the one!

I read this a couple years ago and loved it, but giving it to an unsuspecting friend to read I feel would be a form of assault — so it’s been bottled up inside, festering.

I wonder what book uses the words “abyss” and “vacuum” more than any other? And what author.

I’m looking forward to getting on to Gregorius by Bengt Ohlsson soon, which is a telling of the story from the pastor’s point of view.