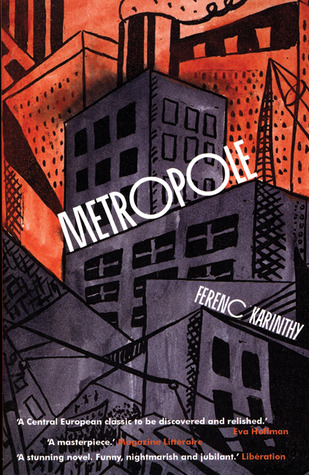

At the beginning of Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler there is a passage on the various types of books we meet in our lives, such as those we haven’t read, those we needn’t read, and those we plan to read. One of the more obscure categories is books that fill you with sudden, inexplicable curiosity, not easily justified, and it’s to this category that I assign Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole (1970), published in English for the first time. Well, perhaps not inexplicable, as its strange premise and eye candy cover help justify the curiosity.

That strange premise sees a linguist, Budai, heading to a conference in Helsinki where he is due to make a presentation, only to wake from the airplane, still hazy, finding himself hustled onto a bus and shuttled to a large hotel. Only then does he realise that he’s not in Helsinki. As to where he is, well that’s a different story, because nobody seems to speak his language, or any of the others his linguistic background allows him.

…he was without friends, acquaintances, indeed documents, and to all intents and purposes, utterly on his own, in an unknown city of whose very name he was ignorant, where no one spoke any language that he could understand even though he knew a great many languages, and where he had yet to find anyone with whom he might exchange a word or two.

One person with whom he has an exchange is the beautiful blonde elevator-operator, although verbally it doesn’t amount to much. Her name is Epepe – although it may be Bebe, Tetete, Egyegye, or Tchetche, he finds it hard to make her out. Budai finds himself drawn to her, not just for her beauty, but because in this indifferent world, Epepe is the only one that seems to acknowledge him, even if their interactions are brief and ultimately frustrating:

They had got round to greeting each other by now and there were occasional signs that she was showing some interest in him too. Twice she addressed Budai as he was about to get out and he smiled and shrugged to show he had not understood. The crowd in that narrow space gave no time for explanations and he was quickly swept away by the others getting off.

Even though he keeps coming back to Epepe, Budai regularly ventures beyond the hotel, into the unnamed metropolis itself:

….the street was no less crowded than the hall, its tide of humanity swirling, flooding, and lurching this way and that. Everyone was in a hurry, panting, elbowing and fighting to get through; one elderly woman in a headscarf kicked him as hard as she could on the ankle and he received a good many more blows on his shoulders and ribs. The traffic in the roadway was equally packed, the cars nose to tail, now stopping, now starting, making absolutely no allowance for pedestrians, as if they were stuck in some eternal bottleneck, engines continually reving, horns furiously blaring…

While this “never-ending rush hour” conjures images of a dystopian cityscape, Karinthy still brings humour to its bleakness, notably through Budai’s explorations. There are queues everywhere and while citizens may find themselves lining up for their everyday rations, they also wait their turn to sit on park benches and, in one comic scene, Budai, takes in a brothel, hoping to communicate there, and finds hordes of men knocking at the door, hurrying him up.

Added to the bleakly comic tone is an undercurrent of melancholia which haunts the novel. Each page, simmers with frustration and helplessness. When Budai thinks he may have a solution, an array of problems announce themselves, his troubles continually cascading into further torment. Nowhere is this more felt than in a huge centrepiece chapter that shows all Budai’s attempts to understand the language spoken around him.

There’s little dialogue throughout the book – indeed, when the local dialect is described as “a language without discernible inflections, a continual jabbering” – there’s little need for it, although Karinthy does allow some of the nonsense (‘Chetchenche glubglubb? Guluglulubb?‘), if only to knowlingly frustrate the reader too. And the large passages of text unbroken by dialogue mirror the daunting nature of the city, a mass of bricks unending.

Like anything that could elicit comparisons to Kafka, there’s an element of horror amongst the absurdity, notably as Budai observes a fight breaking out a subway station:

Could it be that they themselves could not understand each other, that the people who lived here employed various provincial dialects, possibly even quite different languages? In a particularly feverish moment it even occurred to him that each one of them might be speaking his own language, that there were as many languages as there were people.

If it isn’t Hell, it’s certainly a private hell for Budai, and while certain events echo the Hungarian revolution, there are other hints that, beyond the narrative’s veil, there could be more autobiographical elements at work, perhaps even a cameo from the author’s father, the writer and translator, Frigyes Karinthy.

Originally published under the name Epepe, for the aforementioned elevator-operator, a bold and appropriate decision has been made to change the title to reflect the larger scope of the novel’s setting. In doing this we find the city is our anchor, rather than the girl, and in this city that Budai deems “an equation without known quantities”, Metropole more than adds up to the sum of its parts.

Through his blog I’ve discovered that George Szirtes isn’t responsible for changing the title from Epepe to Metropole. As he says, it’s undeserved credit. Oh well. So I’ve changed the post to reflect that. Either way, Metropole feels better. As to why, I can’t put my finger on it, although that’s perhaps of the point of Epepe…or Bebe, Tetete, Egyegye, or Tchetche…

This sounds good, but perhaps a bit too challenging for my current mindset. Do you think I’d enjoy reading it, Stewart?

I don’t think it’s challenging, chartroose. It can be read, I suppose, a number of ways. One way is always at face value. In this it can’t disappoint because it’s an enjoyable mystery, putting you in Budai’s predicament since both are new to this strange city.

Other readings I got from it were, as I say, a masked version of a period in Hungarian history (I read up on it), notably the 1956 revolution. A more explicit book appearing under Soviet rule no doubt wouldn’t have seen print and, if it was seen at all, would have been seen in samizdat.

The other reading I got was personal, the more existential storyline, in which Karinthy questions just how much we, as people, can communicate with each other. We are not, after all, mind readers. And so what we say and what we mean to say are two different things, in turn interpreted differently. This is where I think Budai represent Karinthy, with personal aspects of his life flirting with the story.

So yes, I think you would enjoy it.

Thank you. After my as yet unchosen Finnish novel, which I will interlibrary loan in July, I’ll put this next on my world literature list.

You might have a problem doing that. I don’t think it’s out in the States for a few months yet.

I hope you like it, Tom. Please do let me know. You may also like, if you haven’t read it already, The Invention Of Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares.

As for Ishiguro, I have all of his books on my shelves, although I’ve only read three of them: An Artist Of The Floating World, The Remains Of The Day, and Never Let Me Go. The Unconsoled looms there.

Just my sort of book – amazon here I come. It sounds a little like a favourite of mine – The Unconsoled by Kazuo Ishiguro

Thanks for the reply – I’ll look at The Invention of Morel straightaway! Tom

Hope you enjoy The Invention Of Morel, Tom. It’s certainly up there, still, in my reads of the year, and I’ve recently bought another Bioy Casares novel, Asleep In The Sun.

Off the cuff I’d say that Metropole and The Remains of the Day – wildly different genres of course – are as good as anything fictional I’ve read in the past decade. But then I haven’t read – or even heard of until the above dialogue – Bioy Casares. A treat in store perhaps.

Metropole takes you on a nighmarish journey into a civilisation at once familiar and strange. We all know about modern urban living and its mechanical and brutal impersonality, its maddening bureacracy and its frantic striving towards an unknown goal. But at least we can communicate our frustrations to others and join in a community of sorrow. Budai, the hero of Karinthy’s novel, has not even the consolations of a shared language. Moreover, his frustrations are multiplied by the fact that he is a linguist with a working knowledge of at least 20 languages. Here even his drawings and gestures are misinterpreted. Nobody gives a damn about anybody in this metropolis, least of all about a foreigner struggling to find a railway station, food or shelter, not to mention a way out. All are far too busy going about their inexplicable business. This is our life magnified a hundredfold. Of course the novel also has its local references to life under totalitarian rule, especially under the People’s Commissariat. As in Kafka the individual is an insect desperately scuttling away from the heavy boot of authority. This is a portrait of a dystopia to rank with Orwell’s 1984.

A footnote on the change of title from Ebebe to Metropole. Ebebe is only one of the many possible names of the heroine (or major female protagonist). Further, it would mean little to a reader unfamiliar with the novel’s theme. And in any case she disappears before the end, being swallowed up in the crowd or maybe slaughtered in the habitual carnage, an accepted and obviously acceptable method of birth control in an area of teeming population.

Hi David, good to hear of another reader of Metropole…and of Ishiguro’s The Remains Of The Day, a book I must revisit some time soon. If you do read The Invention Of Morel, do drop by again and say what you thought.

You may be interested to know, if you didn’t already, that Karinthy’s father, Frigyes, was also a writer and NYRB Classics recently put out his record of having a brain tumour, A Journey Round My Skull. I’ve not read it yet, although I’ve sampled the opening chapter.

As heathen-ish as this sounds, I’ll need to read Nineteen Eighty-Four – and Kafka! – for the purposes of comparison. It’s one of those books, since I didn’t do it at school, that you feel you know too well to actually read.

I saw this on Twitter today, that Irish author Keith Ridgeway enjoyed Metropole. It was posted last year, but it took me back to the great experience of reading this book, with fondly remembered details. I wonder what his others were like. And it reminds me to take Karinthy’s father’s memoir off the shelf, too.