When Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio was named laureate for the 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature, I was like many others in wondering who? His standing in English speaking nations, save for a couple of low profile translations in the States, was practically non-existant. And this is an author who has published over forty books since his 1963 debut. It’s been a frustrating wait, then, for publishers in the UK to rush release some backlist titles into print. No doubt translators up and down the country are soldiering away at more of his works.

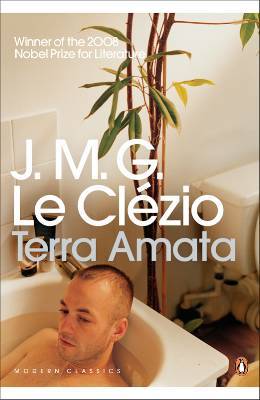

The citation of Le Clézio, by the Swedish Academy, described him as “author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization”- a soup of intrigue, hinting at so much while retaining a cryptic aura. Having looked at the rereleased titles, Terra Amata (1968) seemed to best fit the citation. In fact, it doesn’t so much fit as describe it.

Terra Amata concerns itself with life on earth. It’s the story of Chancelade, looking at his unremarkable life and capturing all the detail and adventures he overlooked.

You’d never done playing all the games there were. A prisoner on the flat face of the earth, standing on your two legs with the sun beating down on your head and the rain falling drop by drop, you had all these extraordinary adventures without really knowing where you were going. A pawn – you were no more than a pawn on the giant chess-board, a disc that the expert invisible hand moved about in order to win the incomprehensible game.

The narrative drops by special points in Chancelade’s life, following from young boy to old man, then pushing beyond. We see the young Chancelade playing in the garden, God to a number of beetles. (“When the boy realized that he was the potato-bugs’ god, with absolute power of life and death over them, he decided to act.”) and teaching them a lesson. We experience his father’s death, follow his sexual development, witness him becoming a father, and ache with his old age.

Le Clézio’s delivery is a hyperreal tour de force, lush and dense, designed to obverload the senses. His focus is on the minute, regularly picking up on grains of sand, pebbles on beaches, and insects in their nests, inverting the microscopic worlds they inhabit to cosmic concerns. Questions of life and death occur, Chancelade occasionaly wrestling with his own mortality, echoes of which appear in the cigarettes he regularly smokes:

It was a perfect action, beautiful as a play. A tragic action. It had a beginning, when the spurting flame met the cigarette. A development, with unity of time, place and action. And when the cigarette was finished, the same hand that had lit it put it swiftly to death, crushing it against the side o the ashtray. And it was really rather as if you were dead yourself, extinguished, suffocated in your own ash, your inside quietly spilling out of your skin of torn paper.

What’s interesting about Le Clézio’s prose is that he is able to capture a new slant on looking at things. In life, everything is an adventure to be embraced full on. He sees objects strewn around as potential communiques between other entities – between men, animals, and the inanimate forces of nature. There’s a language in everything, and we see Chancelade explore this idea in some brief, yet tedious, episodes of Morse code, sign language, and a babelian stew of words.

While much is made of our time on earth, and how little we fully appreciate it, Le Clézio goes beyond humanity, exploring tens of thousands of years ahead to an enjoyable section in a museum, speculating about how we will be remembered, surprisingly quashing humankind’s achievements in favour of guesswork from archaeological digs, much like the conjecture about the real Terra Amata site in France.

Maldec man seems to have lived in communities, in tall concrete houses divided into rooms. His was essentially a working and fetishist civilization. Wars were frequent and deadly, as is proved by certain burial-places recently discovered. These wars were probably due to to racial or religious differences. The civiliation of Maldec man was also ritual, nationalist, and based on the family. It thus belongs to the polymorphic pre-desertic period, which lasted about 5,000 years. It may be that Maldec man was contemporary with the beginning of the great drought which occurred at that time and which caused his civilization to disappear.

Terra Amata, while living up to the aforementioned citation, is perhaps overlong. At just over two hundred pages, it easily feels like three or four hundred. The detail Le Clézio plunges into is often startling and wondrous, but there’s the feeling that he’s retreading the same ideas on occasion, just presenting them differently. There’s a metafictional thread running through the novel, especially evident in the prologue and epilogue, which brought to mind Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler, but doesn’t really bring much to the story itself.

Where Terra Amata succeeds is in holding up a candle to the possibilities of nature, to the potential of life. You may as well use it since you are going to lose it anyway, is the message. Big questions are asked, with no answers forthcoming. Who needs answer, though, when the possibilities are endless? So endless that…

… on the other side of infinity there may be a world just like this one only as if reflected in an enormous mirror: a world where light is black and ants are white and the earth is soft and the sea hard as a slab of marble. A world where the sun is a sooty dot in the sky and volcanoes belch torrents of muddy ice. A world in which you start by dying and end by being born, with the clock-hands all turning frantically backwards. And somewhere in the middle of a big town built downwards into the earth there lives a man perhaps with eyes that look inwards into his head. And perhaps this man has a strange name that can only be said by stopping speaking. Edalecnahc.

While Terra Amata can be reduced to two words – carpe diem – it works because it carries with it the force of infinite experiences. Le Clézio may be an “author of new departures” but he’s also the author of new arrivals on my book shelves.

It is amazing that someone so prolific could be so little known! Thanks for introducing me yet again to another new (to me) author. Having read your fine review, I shall seek him out.

Tom, what struck me as even more amazing was realising, a day or so after finishing, was that he was still in his twenties when he wrote Terra Amata. Most of the newly reprinted books in the UK come from that era, twenties, early thirties. I recently bought another, Wandering Star, that is much more recent, although it still harks back to the early nineties.

Thanks for this review. Le Clezio sounds very… French. I like reading in translation and have usually been impressed by Nobel winners in the past (I was delighted to discover Orhan Pamuk this way, for example). On the other hand, I don’t want to be told that my life would be complete if only I learned to appreciate the joy of smoking. Is there a plot to this book?

Yes, but it’s thin. Essentially, it follows the life of Chancelade, from boy to old man. The unique take is that Chancelade is looking back on the life he blundered through before, marvelling at the rich seam running through it that completely missed him, the first and only time he lived.

I’ve got almost all of his translated books, so hope to get to another one shortly.

Thanks for this post …. I’ve read the book already 4 times. it strikes me. There is always something new …