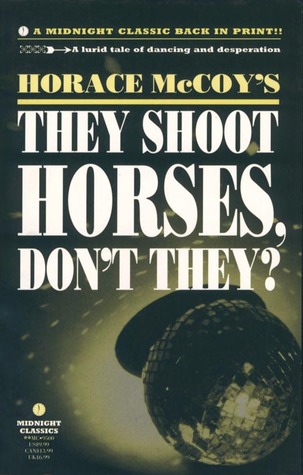

Midnight Classics, as far as I can tell, was an imprint of Serpent’s Tail reserved for publishing forgotten works of pulpy noir and psychedelic fiction. A number of titles were put out in the late 1990s, each boldy declaring that the book was ‘a Midnight Classic back in print’, and all written by authors long forgotten. Names like Gavin Lambert, Stewart Meyer, Rudolph Wurlitzer, and David Goodis. Another was Horace McCoy, probably the best known of the lot.

McCoy’s name has already appeared on booklit where, after a tentative treading of the toes in American noir, with James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, it was suggested in the comments that next up should be McCoy’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1935). Never one to knock back a recommendation (although always one to never get round to reading it) I bumped it up the list, while all the other titles waiting their turn muttered and cursed under their breath.

With horses in the title, I’d long assumed, wrongly so, that the novel was a western of some description. Instead, the novel’s milieu is quite the reverse of the open range, and a new one on me, the claustrophobic world of the dance marathon. Popular in the 1920s and 1930s, these shindigs brought kids disillusioned by the Depression together to dance, for hours on end, chasing the carrot of prize money dangled before them.

One hundred and forty-four couples entered the marathon dance but sixty-one dropped out for the first week. The rules were you danced for an hour and fifty minutes, then you had a ten-minute rest period in which you could sleep if you wanted to. But in those ten minutes you also had to shave or bathe or get your feet fixed or whatever was necessary.

Although mostly flashbacks, the novel begins in the here and now, by outlining its outcome, that of the sentencing of Robert Syverton for the murder of Gloria Beatty. It’s clear to Syverton that the judge means to make an example of him, especially given that the best line of defense he has is that he was “only doing her a personal favour”:

The Prosecuting Attorney was wrong when he told the jury she died in agony, friendless, alone except for her brutal murderer, out there in that black night on the edge of the Pacific. He was as wrong as a man can be. She did not die in agony. She was relaxed and comfortable and she was smiling. It was the first time I had ever seen her smile. How could she have been in agony then? And she wasn’t friendless.

I was her very best friend. I was her only friend. So how could she have been friendless?

Robert and Gloria have come their separate ways to Hollywood, chasing the same dream. Opportunities, however, are few on the ground, and they enter the marathon dance:

‘Free food and free bed as long as you last and a thousand dollars if you win.’

‘The free food part of it sounds good,’ I said.

‘That’s not the big thing,’ she said. ‘A lot of producers and directors go to those marathon dances. There’s always the chance they might pick you out and give you a part in a picture…What do you say?’

‘Me?’ I said…’Oh, I don’t dance very well…’

‘You don’t have to. All you have to do is keep moving.’

During the dance tempers fray, exhaustion sets in, and the contestents find themselves exploited more and more in the name of entertainment. Robert dreams of being back outside, away from the confines of the ballroom, but in writing the desperate situation of this small dance McCoy holds up a mirror to the America of the time, where life itself is punishing and people try to scrape a living against all the odds. The whole narrative is studied with throwaway lines from Gloria, with nothing to live for, wishing she were dead.

‘It’s peculiar to me,’ she said, ‘that everybody pays so much attention to living and so little to dying. Why are these high-powered scientists always screwing around trying to prolong life instead of finding pleasant ways to end it? There must be a hell of a lot of people in the world like me – who want to die but haven’t got the guts – ‘

Even though we know the outcome, McCoy still manages to build up tension in his story. The continued sapping of the dancers’ will through exploitative tasks and the sheer exhaustion they feel builds up crests of conflict that see the dancers regularly whittled down. To this slow burn plot kindling is added, where chapters are preceded by snippets of the judge’s sentence, each in a typeface a little larger than before, serving well the build up of tension.

Loose on description, heavy on dialogue, the novel sets a fair pace, without being a marathon itself, and when its end comes the death of Gloria is treated unsentimentaly, as befits the hardboiled genre. The ending is powerful, for what it is, and I daresay it’s one that will stick in the mind for a long time to come, but there’s the feeling that there could have been more, that McCoy could perhaps have explored the existentialist nature of his narrator, if even just for a few pages here and there, just to get a little deeper inside Syverton’s head. At the same time, the casual enquiry of the book’s title, in context, carries all the weight needed, and it’s the unanswerable nature of the whydunnit that ensures the book’s durability.

Stewart: I know I am being dreadfully Canadian in doing this but I would like to recommend In the Skin of A Lion by Michael Ondaatje as part of your Fante, Cain, McCoy odyssey. You don’t show an Ondaatje on your review page and this book is completely different from his recent work, not post-modern at all. It is set in Toronto in the late 1920s, early 1930s. Unlike Postman or Horses, it explores the opposite of hopelessness (in this way, it is more like Fante) as it concentrates on the work — and aspirations — of an emigrant class who are building a new city. I think you would find it an interesting contrast, particularly since you live in a city where this era would be recent, rather than ancient, history — unlike Toronto. I do appreciate Ondaatje’s more recent work, but as I said it is completely different — Lion is a much more “traditional” novel in the way that it chooses to tell a story. If you are really into depression literature and can find it (and believe me, that will be a challenge) Hugh Garner’s Cabbagetown is a story of depression urban Toronto that is a magificent read. My copy is falling apart at the seams, but still gets reread (with great care).

Thanks, Kevin. I’ve been meaning to try and read an Ondaatje for ages now, but never have. I’ve got The English Patient and Divisadero. I’m aware of the title of In The Skin Of A Lion, but know nothing of it.

As I say above I’m “never one to knock back a recommendation (although always one to never get round to reading it)”, so I’ll certainly take it on board. As to when I’ll read it…

Cabbagetown, I doubt I’ll find. There are second hand copies on Amazon, but I’m not paying that for a second hand book.

Sometime if you find Cabbagetown in a bin buy it — otherwise I’d say let it aside.

I didn’t like Divisdero at all. Much like Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost, I found it forced and not rewarding. The Skin of A Lion is unlike any other Ondaatje work, much less experimental in form but, for me, a far more rewarding read. It was his second novel and he was still staying with more traditional forms — maybe it is me, but I certainly found it more accessible.

I read this book last year. Here’s my review.

http://readywhenyouarecb.blogspot.com/2008/08/they-shoot-horses-dont-they-by-horace.html

I thought it was terrific. I only knew the story from the movie version, which has some great stuff in it. The book added another deminsion to the dance marathon. I’ve been on the look out for more by McCoy since.

Thanks for that, CB James.

Found much? I had a quick scout online and found a few more titles in the same Midnight Classics range.

I have to admit, I think this is an extraordinary work, one of real talent. I see it as a tremendous existentialist meditation of sorts, with Robert as a sort of everyman figure who by blind chance becomes exposed to the sheer pointlessness of life and who takes moral action regardless of consequence (I think there are definite parallels with The Stranger).

He’s doomed (which is not a spoiler) by Gloria, the dance, the incidents that occur during it, and he comes to realise that Gloria is essentially broken. The murder is arguably an act of compassion, which makes it all the more horrible.

The dance marathon works as a metaphor for grinding poverty, but also for life itself. Gloria gets as you note tons of bits of frankly nihilistic dialogue. There’s a lot packed into a few pages.

Great to see it reviewed, and a great review. You can probably tell I’m something of a fan of this novel, but then I have a great love of good noir fiction and noir doesn’t come much more compact but powerful than this.

I also own, but haven’t read yet, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye. I’ll hopefully read that this year (but then I hope to read so much this year…)

I loved this. The fable-like, nightmarish quality to it reminded me a bit of Paul Auster. As you said, there is a genunine historical context to the novella, but that doesn’t stop it working on a terrifying and tangble allegorical level.

Books I’d like to read when printed in Turkey. Looks like an interesting book.

Help!

Does anyone know who owns the rights to the stage adaptation of They Shoot Horses Don’t They? that was adapted by Ray Herman.

Any help would be much appreciated.