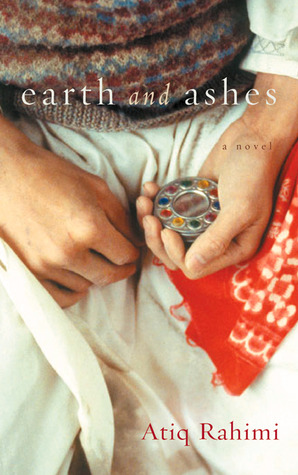

First published in 2000, Atiq Rahimi’s Earth And Ashes is a short novella set in his native Afghanistan (he’s another one of those writers that run away to France, like Milan Kundera and Gao Xingjian when the going gets tough) during the time of the Russian occupation. Told in the second person, it puts the reader into the shoes – or should that be sandals? – of Dastaguir, and elderly man sitting at the roadside with his grandson, Yassin, for company.

The story revolves around Dastaguir (that’s you!) taking his grandson to see Murad, the link between their generations. Murad works in a mine out in the mountains, a barren landscape of loose rock and dust. His mother, wife, and brother have just been lost when their village has been razed to the ground by Russian bombs. Dastaguir, with Yassin, has travelled to the mine to inform his son of the fate which has befallen their family.

The writing, like the landscape, is sparse but conveys much. The translator has brought a certain pathos to the words so that the losses of war imply tragic emotions without explicitly stating. Not only are family members lost but their homes are gone, the war seems to have beaten them, and, since Yassin has lost his hearing from a bomb blast, there is the hint of tradition being lost. Oral history is worthless when passing it down to a boy who cannot hear.

Earth And Ashes is a great little tale, it’s brevity in no way indicative of its power. Despite it’s setting, the fable of Dastaguir, by inviting you to see with his eyes, opens it up to be more of an international affair. The landscapes are blank enough for you to fill in the details; the oppressors mentioned only in name for you to replace with your own.