I became what I am today at the age of twelve, on a frigid overcast day in the winter of 1975. I remember the precise moment, crouching behind a crumbling mud wall, peeking into the alley near the frozen creek. That was a long time ago, but it’s wrong what they say about the past, I’ve learned, about how you can bury it. Because the past claws its way out. Looking back now, I realize I have been peeking into that deserted alley for the last twenty-six years.

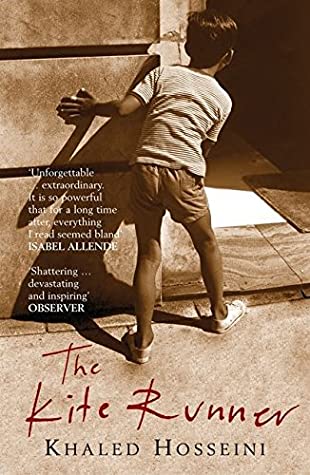

Thus begins The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini’s debut novel; a tale spanning Afghanistan in the seventies to its part in the Twin Towers, passing the Soviet invasion and Taliban rule along the way. The story involves the narrator, Amir, trying to gain his father’s respect by attempting a triumph in the local kite fighting competition. Hassan, his friend and servant, helps him but a life-changing event, for which Amir blames himself, occurs which sees their lives take different paths. When the Soviets attack Amir and his father flee to America via Pakistan where they begin a new life. Amir grows up, graduates, marries, but the thought of his guilt sees him return to Afghanistan, now under Taliban rule, in order to trace Hassan and to right the wrongs of that day in 1975.

Despite the first chapter, a page at most that could be cut, the book begins nicely and sets the stage. Kids play, Islam encourages regular prayer, and the village teems with life. The story continues and we learn about the Hazara, the lowly Afghans used as servants, and how Amir’s playmate, the hare-lipped Hassan, is of this caste. Hassan represents everything the narrator wishes he could be: brave, honourable, and willing to stand up for himself. When Amir needs something, Hassan provides, when Amir is in trouble, Hassan takes the blame, and when Amir is bullied Hassan takes the beating.

It is during this time that Hosseini is at his strongest which, in my opinion, is still rather weak. His characters are alive in their own environment, the play between them is realistic, and the dialogue is nicely garnished with a sprinkle of Farsi. We are also invited to sample Afghani culture as we tour houses and schools, sample the food, visit the cinema, and smile during the kite fighting competition. The only problem here is that the description is so matter of fact that it seems the narrator is listing what he remembers without commenting on any emotional impact it may have caused.

In much the same way that the Soviet attacks caused a downhill surge in the quality of life, the book takes a tumble. Amir’s life in America is a section of approximately seventy pages which, thinking back, seems tagged on. It was as if it were written once the novel was complete and tucked in the centre simply to lengthen the text. Nothing that happens here bears any relation to the rest of the story with the exception of the characters and where the ending is located. I wonder, perhaps, if this part were added to make it not so completely foreign to the mainstream American market.

After the American section the novel doesn’t improve. Amir returns to Afghanistan to right his wrongs and the story becomes more of a catalogue of Taliban atrocities than the emotional narrative it could have been. Eventually, after a series of ridiculous coincidences, the story returns to America where it, thankfully, concludes.

I found the narrator to be too perfect in his recollection of times gone by. Every detail is rendered with incredible certainty, including dreams where he’s not quite coherent, and the descriptions are without sentiment. Nostalgia has never been so dry. Cliché is used prolifically within the narrative although the middle aged Amir does make light of this. He doesn’t, however, seem to realise that his own life story has graced so many movies and books already that, despite being the only Afghan protagonist I know, he is already hackneyed.

The Kite Runner is not a book that I can recommend and I disagree with the critics that are quoted as saying the book was “emotional” when it was so cold that it would take more than a poppy field ablaze to melt its boring heart.

I noticed your comment on the Reading Matters blog, and I had to say:

Thank God!!! Finally, someone who agrees with me. 🙂

Interesting review… But still can’t make up my mind whether I should read it or not, when so many people love it and so many seem to hate it.

I agree with you. So many people say the book “tugged at their heartstrings,” and the book has a “big heart,” but I found that heart false. I just couldn’t believe in the characters or their emotions. Only Amir’s selfishness.

Sometimes I really wonder about the hype over The Kite Runner. On reading the book, it seemed to me that the author had a superb way of narrating the story of Hassan and Amir and has been able to touch thousands of hearts throughout the world. However, the main protagonist of the novel is the Taliban and not the Californin second class citizen Amir or cleft lipped Hassan or the loyalty of the two friends. Without the background of barbarism of the Talibans, the story of Hassan and Amir would have been a simple story of two friends. The inhuman and excruciating tortures performed by the Talibans as portrayed by the author have made the story such a success. Hosseini’s genius lies in projecting the loyalty of two estranged friends in the backdrop of a Taliban ruled Afghanistan.In reality, the atrocities of the Talibans steal the show.

I love Hosseini’s confrontation with pivotal issues that are still prevalent in Afghanistan today. Paramount Vantage, the studio producing the film, just last week, postponed the release date back six weeks in an attempt to ensure the safety of the young actors in the film. The controversial rape scene and the political unrest between the Hazara and Pashtun are showcased in the movie(www.kiterunnermovie.com). It is a shame that the very topics Hosseini discusses in his novel are still, obviously, present today – so much so that a mere independent film could potentially cause drastic ramifications in the Afghan community.

I always smile whenever I hear someone say, “That [book/film/person]

really made me think.”

The first few thoughts are nothing more than awakening from mental

tardiness. The quality and depth of anything more that follows remains

completely unspoken for. Each of us succeeds (and fails) on those

subsequent counts, depending on whether or not we ever become

sufficiently aware of that which we don’t already know enough about to

be able to do some real thinking. We do that by going on to find out

more for ourselves. That is the only way that we can begin to uncover

the stuff that we thought we knew that just isn’t so — the stuff that

mental tardiness is made of.

I think that there is a problem here of expecting “nostalgia” rather

than an embracing a fictional remembrance, for what it is, and then

demanding more “sentiment” from Hosseini’s Kite Runner.

The mistake that precedes the one mentioned above stems from a failure

to begin to grasp and then comprehend what it means to be “of” and

“from” the Afghanistan depicted by Hosseini.

I think there is also a false sense of understanding, on the part of

some readers, who believe that the “universal themes” that lie at the

core of a story are some how too familiar and too readily digested,

without considerable self-examination (as reader) and self-education as

citizens of a very disturbing world.

These responsibilities and obligations of cross-cultural and

non-USA-centric geopolitical understanding and appreciation are too

easily dismissed and shirked by us here in the United States. The vast

majority of us barely gave one crap about Afghanistan before or during

the Soviet invasion and occupation. And too many of us now too readily

fixate on the Taliban (while conveniently ignoring that US government

sponsorship armed and trained that monstrosity), as if there is nothing

more worth knowing about the Afghanistan of today.

Now, if only it were all more *entertaining*, well then…

Witness the short term (December 2007 into late Spring 2008) removal of

the child actors, who worked in the film of the same name, from

Afghanistan, for their own safety.

What an empty gesture (aka publicity stunt) that will turn out to be;

because the real, everyday threats to all of the people in today’s

impoverished and disheveled Afghanistan will be no more diminished in

the coming Spring than they are now. Any eventual repatriation of

those children will not have magically removed any Bull’s Eyes from any

of their backs. Even if Paramount does manage to more permanently care

for these children (as in an Actors Protection Program, perhaps patterned

after some Hollywood Old Folks system of warehousing), what if anything

will have been done for the rest of the children, who are living out in

real life, various aspects of the story that Hosseini has told to us?

What sentiment does that raise for you, Dear Readers??? Will you be

moved enough to do anything at all about it???

I am well acquainted with a few Afghan expatriates who are of the same

generation represented by Amir and Hassan in the book. I only know of

some, who are of Baba’s and Ali’s generation, who admit to speaking

little English (and I speak no Farsi). It does not seem to matter (as)

much here, whether one is Pushtun or Hazara. Some of them, like Hosseini

(at the time he wrote KR) have never been back to Afghanistan since their

exodus via Pakistan. Others have made “trips back” for no reasons other

than commerce/business — in and out, albeit for durations of months at a

time (no one I know goes to Afghanistan just to “take a meeting”).

One thing that I have noticed is precisely how clearly each of these

people recall their own memories of Afghanistan — even when it is

clear that one person’s overlapping memories are in clear disagreement

with another’s. This clarity, to me, is the fierceness with which these

memories are kept. The perfection of imperfection is a manifestation

of living sentiment.

Another thing that has been apparent, to me, is how those who have

suffered immense brutality, first hand, are often times forced into a

stance of internally imposed stoicism, about those specific matters and

their associated triggering issues/memories, as one means of survival. I

make no parochial value judgements whatsoever as to whether or not

that stoicism is healthy or not — it is simply an observed fact. I

suspect that many who are members of Baba’s generation have died early

from the pain of it. An observer will never pick up on this in casual

conversation/interaction; only over time, in trusted company and

according to omissions that are revealed to be steadfastly chronic and

not merely happenstance.

All Hosseini did was to open one particular door in a particularly

accessible manner.

Hosseini, to me, combined some personal experiences and remembrances

with major elements of dramatic fiction in his telling of Kite Runner

to the rest of us — in particular, non-Afghans, who are likely to

suffer major deficiencies in our own individual understanding of and

appreciation for all things Afghan. I used to be one among those and I

still count myself as one pot amidst many sooty kettles. If you happen

to develop cravings or questions as a result of reading Kite Runner,

stop sitting on your brains and go find out.

I think it is a shame that so few such stories are told and celebrated

that so much weight falls on the shoulders of one writer and one book

(or two). And a film.

“The Kite Runner” an awesome book, great attention to details. Every single page made me cry, laugh, warmed up my heart with love, and made me angry… I cried non-stop throughout the book.

I’d be angry if I had to read it again. I don’t quite think I’d stoop to crying. To be honest, I don’t get what’s to cry at in this book. People who say that would no doubt blub over a Mitch Albom or any other sentimental for the sake of it crap.

Hi Stewart–

Uh-oh, my take on “The Kite Runner” is totally different from yours. I think it’s a great story, not a great novel. It must be looked at in context and examined as a basic tale of betrayal and redemption aka a modern morality play. Its simplicity is what makes it so appealing to so many, including myself. I did find the writing to be stilted and just plain juvenile in places, but that added to the appeal as well. The narrator was speaking of events that happened when he was a child so the narrative should not be on a par with someone like Hemingway. Sometimes it’s refreshing to read something that you can whiz through and feel a connection to without having to analyze it to death.

I read in a recent issue of National Geographic that the Hazara are really starting to build better lives for themselves and their communities. Pretty cool! Here’s the link if you’d like to take a look:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/2008-02/afghanistan-hazara

I can’t vouch for it’s quality, but an online acquaintance recently done this challenge and did Andorra by Michèle Gazier for Andorra. I don’t know whether it’s a short story or an essay, but apparently it comes from a volume called Views from the Bridge of Europe – probably an essay – although I have no idea as to its availability.

Here full list can be viewed here.

Hi Stewart, thanks for the lovely comment on my blog.I’m loving my challenge, though you may have noticed that I am stuck at country # 4 – Andorra. Any suggestions on books (in English) written by an Andorran author? Most people think I should read a book about Andorra, but that’s not really what I want to do. I’d love any suggestions you might have!

I’m glad I stumbled upon your review. I read A Thousand Splendid Suns first and was completely underwhelmed. I thought the whole novel was cliched and formulaic, the characters unreal. Although it did make for smooth pop reading. Anyway, I often wondered if it was just not as good as The Kite Runner, and have been going over in my mind whether I should read this or not. Apparently, both books share the same qualities, so it would be best if I didn’t read this one. I’ve never found a negative review of this before, so although I’m sure it isn’t that awful, I’m also pretty sure now that it isn’t something I’m going to truly love either. Thanks!

You’re welcome, Claire. When I read this book (back in 2005, despite the date here) I had no idea what to expect. I think it may have been the book that finally made me cynical toward hype (even if still a mug for it!) and, being so bad, left me without the need to ever read Hosseini again. I’m not surprised that it has done so well, as it ticks all the shallow sentimental boxes (here’s another example) but I don’t really trust it as a decent example of Afghan literature like, say, Atiq Rahimi’s Earth And Ashes was.

I think you perfectly capture why I couldn’t finish this book. Of course my first problem was listening to the audio, narrated by the author which is sometimes not a a good idea. But I so hated Amir that after his betrayal I couldn’t stand listening any more. I think it was the lack of emotion that you describe — there was nothing other than the story to capture my interest. And I didn’t like the story.

I’ve just read a few of your reviews and it looks as though we have polarised views on books!

I loved The Kite Runner. I can see from your reviews that you favour great writing over a good story. I love it when books are able to combine both, but I read to be entertained, and love anything with a good plot.

Have you read Home by Marilynn Robinson? I think you’d love it!

I’m not fussy, Jackie. Good writing, good story, but writing always comes first. If the writing isn’t ‘good’, then it’s going to affect judgement on the book as a whole. Good writing doesn’t have to mean poetic observations and verbal strainings, but that it does the job it sets out to do and does so in an engaging way without compromising the believability and ideas that the author is playing with.

As for Marilynne Robinson’s Home, no. I read Gilead a few years back and did not like the book one bit and, seeing it’s connected in some way with Gilead has initially put me off ever wanting to read it. I recently picked up Housekeeping though.