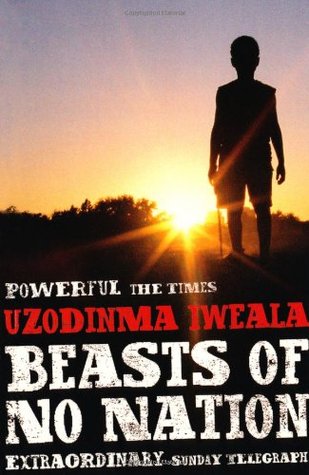

Trying out a debutante author can be a huge step into the unknown but, with praise from Rushdie, Ghosh, and a number of British broadsheets adorning the cover, it’s a step I decided to take with Beasts Of No Nation by Uzodinma Iweala, an unsentimental study of war through the eyes of a child soldier. And it doesn’t disappoint, providing a detailed series of events that add background to the stories of civil war in Africa that we often see in the news, although its arching tale of chilling conflicts and unspeakable acts is somewhat let down by a somewhat fortunate conclusion – for the character, that is, and not the reader.

Agu, our narrator, tells us not where he is from or how old he is but begins by giving an account of how he became a soldier when his village was raided and he ran from the scene into the clutches of a band of rebels. Then, before he knows it he is following the command of two men (early twenties, at most) called Commandant and Luftenant as they lead their band of boy soldiers across the nation for the cause.

The cause itself is never mentioned; Agu doesn’t actually know what he is fighting for. He is only able to differentiate between the time before war came (which becomes more and more a faded memory) and now. But, to aid the cause, Agu’s troop find themselves killing at random, raping women, burning villages to the ground, and stealing. Beasts Of No Nation is a catalogue of man’s inhumanity to man in the time of war and its lists expands to include prostitution, cannibalism, and child sex abuse. While never explicit in his description, it’s the suggestion of these acts, as described by Agu, that resonate.

As a soldier, Agu doesn’t know what he is meant to be doing. In fact, the only soldiers who seem to have a clue are Commandant and Luftenant:

Commandant is yelling, TENSHUN and I am seeing that now all of us is standing here and all of us is forming tenshun very quickly. Then, Commandant is saying to us that we should be behaving ourself and looking sharp and resting well well that we will be knowing what is happening in some time. Everybody is listening, but nobody is really understanding what he is saying about moving to the front and fighting the enemy in this place or that place because I am never seeing this place or that place for my whole life. Anyway, it is not mattering too much because I am just following order and not having to do anything else. After he is shouting on us like this, he is telling us to dismiss and make camp.

Rather than be soldiers, the kids are more interested in looking like soldiers. They carry guns or machetes and wear uniforms to show status. Uniforms, itself, becomes a loose term since any clothing they can find (soldier, policeman, etc. ) is taken from the dead and worn with pride.

As you can tell from the quote above, Agu’s narration is given authenticity by mixing tenses, incorrect use of plural and singular terms. The effect, at times, can be poetic and his voice assumes a wonderful rhythm. There were a couple of times where I had to read the sentence again to work out what had just been said. My only criticism of using this style is that Agu has a limited vocabulary and I noticed him using the same similes (like bullets; like ants) on multiple occasions. Fair enough, given that it’s the character’s voice, but it felt like the narrative could achieve more with some extra vocabulary.

If I was to have any major criticism of Beasts Of No Nation it is that Agu is surplus to requirements within his own narrative. The conclusion of the novel (or, at least, the penultimate conclusion) is perpetrated by another character which renders Agu as observer and not master of his own destiny which one would hope for in a character study.

Of the aforementioned reviews on the cover of the book, the one that rings true most is Rushdie’s, when he says “this guy is going to be very, very good”. It’s a fine little novel, showing some truth about conflicts we rarely think of when war is mentioned, and gives a voice to the images of child soldiers splashed occasionally on the news; but it’s not quite perfect.