When it comes to fiction I tend to have a preference that excludes novels revolving around war. No real reason – it’s just a topic that has never interested me. But, looking back at some of the novels I’ve read, it’s hard not to see that I’ve read my fair share (Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains Of The Day, for example, or John Steinbeck‘s The Moon Is Down), even if the war element appears tangentially. So it seems ludicrous that I should have, despite glowing recommendations, wanted to bypass The Welsh Girl, the debut novel from Peter Ho Davies. I’m glad I didn’t.

The Welsh Girl is a universal tale told within a wartime setting and it does so with such ease that it’s hard not to be swept away at the joyous prose and warm to its memorable cast of characters. To add to this, there’s depth to be had in the novel’s exploration of love, nationality, identity, and loyalty, as it braids the lives of its three main characters until they all come together in a single strand.

Set in rural Wales in 1944, The Welsh Girl opens with Captain Rotheram, a German Jew working for British Intelligence, interviewing Rudolph Hess in an attempt to assess his sanity for trial. After a time he gets orders to go north to a village where the staunchly nationalist population haven’t taken too kindly to the English soldiers on their turf and are further enraged that there’s a prisoner of war camp being built on their doorstep:

…the sappers are still called occupiers to some. It’s half in jest, but only half. The nationalist view is that it’s an English war, imperialist, capitalist, like the Great War that Jack fought in and from which he still carries a limp (not that you’d know it to see him behind the bar; he’s never spilled a drop).

In this prisoner of war camp there’s Karsten Simmering, a German soldier with some English at his disposal, who suffers the weight of his decision to surrender, believing it cowardice and wondering whether it would have been better to die. There, through the wire fence, he befriends Jim, a young evacuee from Liverpool, their regular exchanges his one connection with the outside world.

And then there’s Esther Evans, the Welsh girl of the title. At seventeen years, she’s the interest of many a boy’s eye, notably the postmistress’s son, Rhys, who has gone off to fight and Colin, an English sapper who her staunchly nationalist father would object to. While she works at the local bar, Esther’s dreams reach beyond the Welsh valleys to the romance of the world beyond:

She has her own dreams of escape, modest ones mostly – of a spell in service in Liverpool like her mother before her, eating cream horns at Lyons Corner House on her days off – and occasionally more thrilling ones, fuelled by the pictures she sees at the Gaumontin Penygroes.

These three characters, by virtue of the war, are brought together in the tangle of wartime drama. Questions are asked: on the nature of what it means to be Welsh, British, German, or Jewish; on whether surrendering is an act of cowardice; and on whether love truly knows no barriers. And surrounding them all as Davies narrative gets to the heart of these matters, is a supporting cast that flesh, but by no means pad, the story out, given it further depth and instilling equal parts humour and pathos.

The author’s prose, while seemingly dense, is actually light to read, and has a way of capturing a scene that with a few strokes, lets you know what’s happening, what people are thinking, in addition to colouring it with wonderful observations and attention to detail:

She settles herself, and he puts his hands in the small of her back and shoves firmly to set her off, and then as she swings he touches her lightly, his fingers spread across her hips, each time she passes. ‘Go on!’ she calls, and he pushes her harder and harder, until she sees her shiny toe tops rising over the indigo silhouette of the encircling mountains. When she finally comes to a stop, the strands of dark hair that have flown loose fall back and cover her face. She tucks them away, all but one, which sticks to her cheek and throat, an inky curve. He reaches for it and traces it, and she takes his hand for a second, then pushes it away. He’s on the verge of something, but she doesn’t want him to come out with it just yet, not until it’s perfect.

With The Welsh Girl being a debut novel (after two short story anthologies), it’s a huge surprise how assured and confident the author is with his material, with his characters, and with the questions he asks of his novel. It’s no surprise that Granta in 2003, despite not having a novel to his name, labelled Davies as one of Britain’s best young novelists, a tag he has surely delivered on. And with The Welsh Girl being on the Booker longlist, further plaudits and success must surely beckon for this fantastic writer. I certainly will be looking into his previous work – one promise I won’t be welshing on.

This sounds good too. So far I havent read a bad review of any of the Booker longlist titles. Surely theres got to be a dud in there somewhere.

Interesting about the war thing – I’m never too sure about war themes either. Maybe its about tackling such a big issue, and how to do it well, and tell an original story without falling into cliche.

I think it’s just me being silly, really. When I think of war novels I get these images in my head of weapon fanaticism complemented by sections discussing military tactics. What I’m really thinking of is maybe war non-fiction, which I’m not one to read, as every novel which touches upon war has never contained any of the above.

*groans*

I know what you mean about war themes.

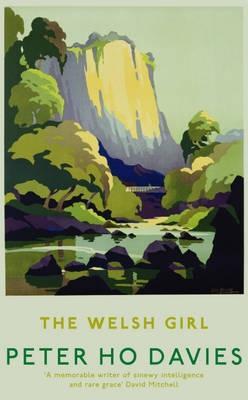

I’ve read tons of great reviews of this book, and this is no exception, and I have a lot of thoughts about it, but all I can think right now is that the cover is awful. I am going to read this soon, I think.

Awful? Awful? I think it’s a lovely cover. Nicely stylised, the river almost symbolic of the divide expressed within, of sides.

No, despite the symbology (I hadn’t noticed myself) that cover is still awful.

I just finished reading this book yesterday and really enjoyed it. I particularly enjoyed it for the range of emotions it covered–Esther’s guilt about getting pregnant, Karsten’s shame at having surrendered, etc. And as you’ve noted in your review, it was just a very nice narrative. I like that Ho Davies worked in some jokes. Can’t say enough about this book–just a very, very enjoyable read.

Glad you enjoyed it. A colleague recently asked for book recommendations – she’s not much of a reader – and this was one of the titles I suggested. Whether she reads it or not, who knows, but it’s nice to be reminded of it.

As I’m trying to add some short stories to my diet, I wonder if it’s worth adding one of Ho Davies’ prior collections to my list. Has anyone read them?

I read “The Ugliest House In The World” quite a while back. I remember liking it at the time but can’t recall any of the stories very clearly now. I read an awful lot so that’s not surprising. What I remember is the variety of the collection–stories told from quite a few different points of view and set in different time periods. A lot of reviewers, I’ve noticed, tend to like that sort of thing; as though it were proof of the author’s versatility but I generally like story collections that are more unified in terms of the characters and settings. Just my taste I suppose.