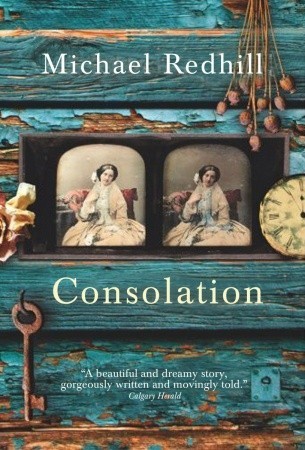

Canada’s Michael Redhill was reportedly surprised to find his second novel had been longlisted for the Booker this year. If the content was given over to errors such as the misprint on the inside cover then I’d have been surprised too. But thankfully Consolation’s prose shows no such slips and it runs with two distanced narratives detailing Toronto past and present that eventually come together by the novel’s close.

Professor David Hollis, in his latter years, was suffering a debilitating disease. Having been ridiculed by his peers for his latest claims, concerning a boat under a landfilled lake, he drowns himself. Left to pick up the pieces and determined to prove him right is his wife, Marianne. Helping her is John Lewis, her daughter’s fiance, the attention shown to her mother – and her father’s claims – rocking the boat. But if they don’t prove those claims then it’s possible that the proposed stadium could bury forever the glass plates of early photos documenting Toronto rumoured to be on board.

Meanwhile, back in the 1850s, Jeremy Hallam, late of England, has come to Toronto to expand his father’s apothecary business. However, that trade already has its fair share of aggressive competitors and, after a meeting with Sam Ennis, an Irish photographer, and his model, Claudia Rowe, Hallam takes his first steps into the world of photography, a path that seemingly leads to the sunken ship and the photos speculated 150 years hence.

Of these two narratives, despite both being well polished, the historical sections shine more. Perhaps the distance helps – presenting times past surely requires more effort to evoke than does modern life with its cars and televisions. There’s a need to create a sense of place – warm coals do it; central heating is taken for granted. And so, to make the modern (well, the nineties) sections more interesting, it’s dialogue that spurs them on – exploring the triangle of John, Marianne, and daughter, Bridget.

While Hallam follows his photographic ambition and Lewis chases the claims of David Hollis, the star of Consolation is the city of Toronto itself, appearing both in its infancy:

Streets paved with little more than the accumulation of grit pressed into them by boots. Wooden sidewalks put together with penny nails. Tar-acrid log shanties with bank buildings made of Kingston stone in their backyards. German and French spoken freely in the streets and canoes out in the lake with actual Indians in them, spearing salmon at the river mouth. Then that same lake, frozen to stillness between December and April, ice-clenched with nothing coming in or out of it. And centred in it, with misplaced pride, a stuttering attempt at making an English town out of nothing, like a voice straining to be heard from a great distance. It would actually be funny, Hallam had thought, if he didn’t have to live here.

And in more mature years:

North of the main thoroughfare, the big houses that had been built in the fifties and sixties were slowly being returned to their original forms, with two-career families snapping up the properties at second-best prices and refurbishing to their hearts’ contents. But south, the houses were smaller; they were still better earners than sellers, and the area was full of tenants.

At its core, Consolation is about history. It looks at how the past only really means something when it is the past – the present doesn’t matter. One only has to imagine the bewildered expression on the Deputy Mayor’s face when Hallam shows him recent portraits of Toronto. (Why would someone do such a thing?) Also given the spotlight is the passage of time: history is always being created and nobody cares about it, even the hotel room where, once you’ve checked out, your presence is wiped away, forgotten.

Consolation is certainly a story of two halves and, with a twist thrown in (perhaps a tad predictable) it gives a good account of itself. Its strengths are in its attention to detail and the wonderful sense of atmosphere in the historical sections, and, while Redhill’s dialogue is well wrought, the modern sections are less engaging, in part because the characters were not strong enough to be noticably individual. I enjoyed this novel but, like the aforementioned hotel room, I suspect that with the next read this novel will be easily forgotten, which I’m sure is no consolation to the author.

The general concensus seems to be that the early sections far outshine the latter. Which is a shame, because I quite like books that do dual narratives.