Some books seem to capture the imagination and transcend the boundaries of fiction. Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black would appear to be one such novel, given that it’s been adapted for both stage and screen. In fact, the stage version has been playing in London for almost twenty years. There must be something about it that makes it such an enduring tale, so I decided to find out.

It begins with an elderly man, name of Arthur Kipps, listening to his stepchildren share ghost tales one Christmas Eve, as per tradition. When pressed to share his own story, he refuses. And then the narration reflects back to when Kipps was a junior solicitor and was sent to represent the firm at the funeral of a Mrs Alice Drablow, and, in the absence of heirs, to subsequently sift through her papers for information relevant to the now uninhabited property.

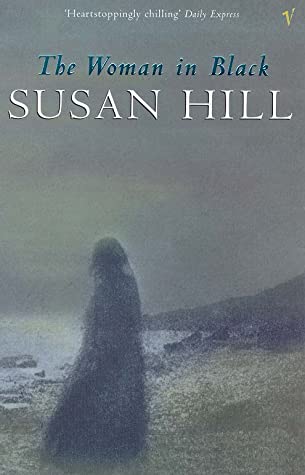

On arriving in the coastal town of Crythin Gifford Kipps finds the locals secretive, and it’s obvious they know more than they let on. Although he’s staying at a local inn, he finds himself spending most of his time at Eel Marsh House, Drablow’s creepy old home on an offshore island accessible only when the tide is recedes. And when Kipps represents the firm at Drablow’s funeral, he sights a mysterious mourner, a woman all in black, which leads the novel, and its main character, along a supernatural path culminating in a dramatic yet inevitable finale.

It’s no secret that Hill has returned to the stories of M.R. James when writing her ghost story, one of the chapters goes so far as to borrow a title. But thankfully, like the stories that open the novel, there’s little of the expected supernatural staples knowingly listed:

…of dripping stone walls in uninhabited castles and of ivy-clad monastery ruins by moonlight, of locked inner rooms and secret dungeons, dank charnel houses and overgrown graveyards, of footsteps creaking upon staircases and fingers tapping at casements, of howlings and shriekings, groanings and scuttlings and the clanking of chains…

What there is, then, is a slow burning sense of menace. Sure, there’s ghosts and some spooky goings on – and a town unwilling to speak about them – but its the pages between visitations as Kipps tries to makes sense of his predicament and try to understand why such other-wordly goings on are, well, going on. Needless to say, an explanation is given but this doesn’t weaken the story as it gives substance instead – and there’s still the question of how such things are possible. Like all good supernatural fiction, they just are.

Hill’s prose throughout maintains a gothic tone that superbly captures a post-war village distanced from the world at large where common sense comes after superstition. Characters, when asked straightforward questions, rightly pause during speech to give the needed sense of foreboding, the and descriptions are sorrow-tinged and abundant in adjectives without being unpalateble:

It was indeed a melancholy little service, with so few of us in the cold church, and I shivered as I thought once again how inexpressably sad it was that the ending of a whole human life, from birth and childhood, through adult maturity to extreme old age, should be here marked by no blood relative or heart’s friend, but only by two men connected by nothing more than business…

While The Woman In Black isn’t a groundbreaking piece of fiction – and it doesn’t set out to be – it certainly invigorates my interest in the supernatural. Its gothic atmosphere didn’t seem forced and although it was grim, in a perverse twist, I found it enjoyable. And although there’s no doubt a mountain of ghost stories out there to be read, I’m happy to start with a Hill or two.