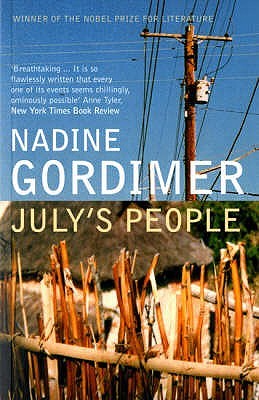

My previous experience of Nadine Gordimer was with last year’s Booker longlisted Get A Life. That book, to me, was so full of stunted sentences, lacked narrative focus, and was excruciatingly boring that it’s a wonder I would want to read another. But, sometimes, to get the measure of a difficult author (and being a Nobel laureate is usually a good marker of being one) you have to go back to previous works when the style was not so prevalent. With July’s People I don’t think I went far enough back as there were still many of the stylistic tics I hadn’t enjoyed in Get A Life, but this novel was a better and more coherent read.

July’s People is set after the Soweto Uprising in a South Africa where the situation has become anarchic, with white people being forced from their homes, sometimes killed. The Smales family, Bam, Maureen, and their three children believe themselves “lucky to be alive” when they escape to rural South Africa and stay in a mud hut as guest of their servant, July.

It is here, away from the city, that the Smales come to realise the difference between the white and black people of South Africa, for where they are all about the money, the poor have different needs:

She saw how when she or Bam, who were completely dependent on these people, had nothing but bits of paper to give them, not even clothes – so prized by the poor – to spare, they secreted the paper money in tied rags and strange crumpled pouches about their persons. They were able to make the connection between the abstract and the concrete.

July’s People shows the descent of the Smales family as they try to make what they can of their life amongst the poor black community. While July remains servile to them, the gulf between white and black people is slowly dissolved to the point where it is the white family who is found to be helpless while the black people are resourceful to the last. In a life where everyday necessities such as toilet paper, sanitary towels, and groceries become luxuries, the Smales make an effort to understand their new environment but ultimately remain trapped, never quite knowing how to get out.

Mercifully, the prose in this novel is much easier to read than Get A Life (and, I presume, later Gordimers). And while the dialogue can still throw you sideways for a moment, it’s quite easy to regain the thread. Stylistically, rather than use quotes, Gordimer has opted for dashes opening and closing speech. During periods of extended interaction between characters it can be a tad unwieldy, but is ultimately readable. There is also the occasional fragmented sentence but nothing untoward that really hampers the text.

In fact, July’s People has much enjoyable writing. When Maureen, our window on the world, isn’t philosophising, there come a series of descriptions that evoke the difficulty of trying to live a normal life in a world outside your comfort zone, and of how natural that world is:

They made love, wrestling together with deep resonance coming to each through the other’s body, in the presence of their children breathing close around them and the nightly intimacy of cockroaches, crickets and mice feeling-out the darkness of the hut; of the sleeping settlement; of the bush.

Gordimer also takes time in the novel to find stylistic flourishes, such as the initial car journey when the Smales flee their lives – a piece of writing that wonderfully captures the bumpy journey off road and the angst of the ordeal as a whole:

People in delirium rise and sink, rise and sink, in and out of lucidity. The swaying, shuddering, thudding, flinging stops, and the furniture of life falls into place. The vehicle was the fever. Chattering metal and raving dance of loose bolts in the smell of the childrens’ car-sick. She rose from it for gradually longer and longer intervals. At first what fell into place was what was vanished, the past.

My reading of July’s People was very much like that car journey. There were moments where I found my mind drifting as I read it, not taking much in, but, as I warmed to the prose style, I found myself finding more and more of it followable. Those lapses, however, may have lost the novel’s full effect for me but it’s certainly piqued my interest for some more of Gordimer’s work, for it’s a great mix of gritty reality and symbol all wrapped up in a style of her own making.

Then, you must read ‘The pickup’