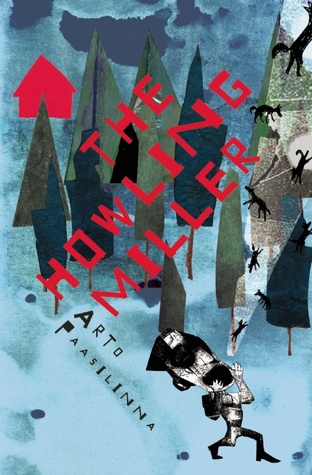

When it comes to choosing a book there are all manner of things that can – and do – influence my choices. An interesting cover is one such way to grab my attention, as is an alluring title. And then there’s the matter of my ongoing mission to discover new writers. Of those three, Arto Paasilinna’s The Howling Miller (1981) ticks each box – and so it was a dead cert to be read. And the sooner the better.

Set in post-war Finland, a man named Gunnar Huttunen (“as lean as he was tall”) arrives in a rural village and takes control of the local mill, rundown due to the war, and restores it to past glories. For this the villagers are happy to have him and, of an evening, he proves great company with his ability to mimic animals – cranes, bears, elks – but this all changes when, prone to mood swings, he finds a release in howling “from dusk until the early hours and, if it were carried on the wind, every dog for miles around would answer his desolate cry.”

And this is just the opening pages, to which the villagers react by deciding that, since he won’t conform with their wishes, he must be mad. It’s not long, then, before the local doctor has officially certified him and he’s transferred to “the loony bin” from which, with the help of an inmate, he soon escapes. What then plays out is an extraordinary conflict between Huttunen and the people of the village as they try to out him from the woods in which he hides in order to return him to the asylum. As the hunt for Huttenun escalates in scale, all he has to side with him are the local postman – also the local drunk – and Sanelma Käyrämö, his girlfriend who, because of his madness, isn’t quite willing to settle down lest they “have a baby, the mad child of a mad man.”

It’s a riotous novel, full of deadpan humour told in a comic style that, as the opening paragraph suggests, comes across like a fable, throwing in some period references:

Soon after the wars, a tall fellow appeared in the canton who said his name was Gunnar Huttunen. unlike most of the drifters who came up from the south, he didn’t go to the forestry department looking for work digging ditches, but bought the old mill on the Suukoski rapids of the Kemijoki River. This was judged to be a hare-brained scheme, since, having stood idle since the 1930s, the mill had fallen into a state of extreme dilapidation.

If I were to have any complaint of The Howling Miller it’s only that the translation felt adequate and nothing more, coming as it did from Finnish via a French translation, an approach I felt similarly lacking in Ismail Kadare’s Spring Flowers, Spring Frost. There’s always that sense something gets lost in translation, but one wonders what gets lost in translation of the translation. Certainly not the humour or the tone, in this case. But Paasilinna’s other novel currently translated to English, The Year Of The Hare is direct from Finnish. So why not this?

But that’s a small grumble as the gist of the novel is still there and it’s enjoyable, maintaining interest all the way through, the narrative never waning, as it winds its way through themes of persecution, corruption, and madness with more subtle content concerning agrarian principles, demonstrating Paasilinna’s seeming love of nature. The Howling Miller, as a read, has worthwhile concerns to explore but here there are no answers – or attempts to assert opinion – here; just a straightforward tale that may just have you howling too.