Having read a novel by John Fante a couple of years back I was interested in reading something by his son, Dan. From what I understand, Fante fils is more in the mould of Charles Bukowski, who was apparently inspired to write by Fante père. With an output spanning novels, plays, and poetry, the lazy comparison is there. And having not yet sampled Bukowski, I’m afraid I’ll have to remain lazy on that.

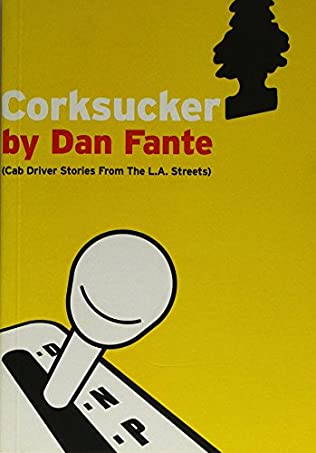

But what better way to introduce oneself to an author than by diving into a collection of short stories? Corksucker (2005), or Corksucker (Cab Driver Stories From The L.A. Streets), to give it its full title, is Fante’s first such collection (published as Short Dog in the US) and follows the thread of Mickey Di Salvo’s life, which centres around, as the title implies, taxi driving, as he goes from one scrape to the next, grasping each day by the scruff of the collar and trying to hold on, despite alcoholism, rocky relationships, and a perennial lack of cash.

Hack driver is the only occupation I know with no boss and because I have always performed poorly at supervised employment, I returned to the taxi business. The up side, now that I was working again, was that my own boozing was under control and I was on beer only except for my days off.

Di Salvo, an alter-ego of Fante, first person narrates each of the eight stories in Corksucker. While he wishes he weren’t a cab driver and depends on alcohol to get him through the day, he’s always working on his novel or scribbling down a poem a day. With literary dreams never being realised and a tendency to the bottle, Di Salvo isn’t the most stable of characters and this comes to the fore, often providing the stories’ impetus. And his style of narration is wonderfully crude, with good humour, and the occasional epiphany draped in expletives that, despite their frequency, never seem excessive.

In Wifebeater Bob, Di Salvo metes out justice to a hotel doorman who always wants a cut of the taxi drivers’ takings, while at the same time trying to raise the cash to retrieve his manuscript, which his girlfriend is holding to ransom. Then, in Mae West, our narrator leaves the taxi alone for a bit and deals with his relationship his girlfriend, a different girl from the previous story. If he’s going to go on living with her then she wants him to sort his drinking out, to try rehab, which he does, learning a trick or two along the way. And if he’s going to continue living with here, there’s the matter of her dog, Banana, which plain doesn’t like him:

In the beginning, the month I first moved in, I’d made up this game: I would hold up two fingers to the animal in a sort of ‘V’ for victory Nixon-type signal, then whisper his name. “Ba-Nana.” “Ba-Nana.”

It pissed the dog off. I knew it pissed him off, but I did it anyway. Mostly it was when I was on the juice that I did it but, in retrospect, I can see that I’m responsible for instigating our mutual hatred.

Caveat Emptor and Marble Man, one a story where sexually transmitted diseases are an occupational hazard and the other where Di Salvo takes a break from cab driving, tries telemarketing, and ends up taking his boss’s wife (“blond, silicon-titted”) to view a potential sublet. These were rather lightweight and, truth be told, I remember little of the latter merely hours after reading it.

Of the other stories, Princess is memorable for its tale of a junky couple feeding an insatiable python whose appetite for food isn’t affordable, especially when they’d rather spend it on getting high. And Thebobby lapses into an enjoyable screenplay which, given that a character mentions that Di Salvo should write a screenplay about him, is a nice little trick. Renewal, where he comes round from a blackout in a cinema, with trousers round his ankles and a transvestite nearby inspires a Did I? moment, but soon slips into a visit to City Hall to get his license renewed. And closer, 1647 Ocean Front Walk, brings Di Salvo the closest he’s been to love, ending on a sad, optimistic note, which takes him away from cab driving for good:

I hated being stuck driving a cab. Since taking the gig again, my life had been drained of meaning. Stalled. The taxi business extracts the vital fluids from a man’s body twelve-hours-a-day, six-days-a-week, a drop at a time. L.A. cab driving isn’t useful work. It is human refuse relocation, the transportation of decomposing flotsam from one plastic fast food neighborhood to the next.

While I prefer the US title due to its dual meaning – a cheap drink or Di Salvo, himself, who is touchy about his size – it’s no matter as it’s the contents that ultimately matter. And each page of Corksucker is a fun, booze-soaked exploration beneath L.A.’s shiny facade, showing, even amongst all the oddballs he encounters, the humanity within. It’s worth jumping in for a ride, and while I wouldn’t usually advocate it, it’s probably the safest you can ever come to recreational drink driving, from one book neighbourhood to the next.

If you enjoyed Corksucker you’ll probably like Fante’s novels as well. There are quite a few similarities: alcoholism, destructive relationships, telemarketing jobs and ‘just how autobiographical was that!’ moments.

He uses the same alter-ego style as his father and Bukowski, with the narrator of his novels called Bruno Dante – can you see what he’s done there? You’re right about Bukowski being a major influence btw, with perhaps a dash of Irvine Welsh too?

Thanks, The Bad Bohemian.

I think I do intend on getting Fante’s Dante novels and finally getting a taste of Bukowski. But first, I think I’m going to return to John Fante, perhaps beginning with a reread of Wait Until Spring, Bandini as I remember very little of it other than I enjoyed it at the time.