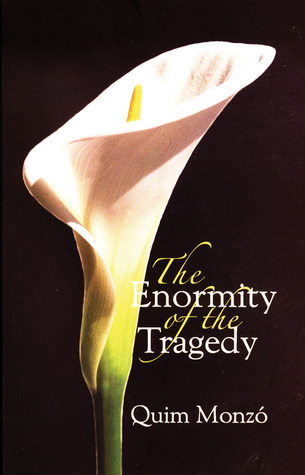

There’s probably a lot of jokes than can be made about an author named Quim translated by someone called Bush and, with that in mind, I’ll try and give them a wide berth. So, by way of introduction, the Catalan writer Quim Monzó’s first novel appeared in 1976 and since then has made a name for himself for his novels and short stories but is rather unknown in the English speaking world. Recently published, The Enormity Of The Tragedy (1989) is the first time, as far as I can tell, one of his novels has seen its way from Catalan to English. With this in mind I was curious as to how it would stand up.

Quite well, it turned out, but not quite so well as the penis of main character, Ramon-Maria. When he wakes one morning after a night of failed passion, the damn thing just won’t go down. While it makes him more attractive to women, Ramon-Maria’s predicament is anything but the dirty joke it first seems. His problem is rare, incurable, and leaves him only weeks to live.

Ramon-Maria, at first, does what most learning of such news would do and treats the diagnosis with disbelief:

Seven weeks. He felt an emptiness in the pit of his stomach, an emptiness he preferred to think was caused by shock not by distress or fear. He couldn’t altogether believe it was true. It couldn’t be, he thought, now he wsn’t facing the doctor. Because he’d not opened his mouth in front of the doctor. Seven weeks. It seemed impossible. Surely if he did it all again, if he retraced his steps as if he’d never been to the doctor’s, things would be different. He’d do that. He’d walk to the corner of the street, turn around and come back to the building, press the button to the eighth floor, go back to the surgery, ask for Dr Puig-Amer again, be given the inconsequential results of his tests, the doctor would say that one of these days his permanent erection would disappear, everything would go back to normal and he’d once again be a mortal, without an expiry date.

But, after a second opinion, he’s resigned to his fate and sets out to make his last days the best of his life. He takes out a mortgage and, rather than buying a house, uses the money to sample the best of everything.

Running parallel to the story of Ramon-Maria, is that of his house-mate and step-daughter, Anna-Francesca. She’s young, discovering her sexuality, and hates Ramon-Maria. Innocent of his problems, when she’s not stealing cash from his wallet, she’s entertaining the thought of killing him:

What hypocrites people are who claim man is by nature a peaceful animal! Man is an animal who needs violence as much as any other animal and puts the brake on only (sometimes) because he’s been educated. How many years more would she have to suffer him if she didn’t kill him? Twenty – ten at least? Or even thirty? She couldn’t waste years and years (hey, the prime of life!) waiting for the ten, twenty or thirty years until he died. If he died (say) in twenty years’ time she’d be thirty-five! She’d be a clapped-out old woman. She must act now.

Either way, as the title implies, you know both novel and Ramon-Maria’s life are not going to end well, but the meandering prose sweeps you along wondering who will win out: his terminal illness or Anna-Francesca. The novel’s content is strange in that the important incidents are given short shrift while the banal musings of the characters comes to the fore. Events are sometimes implausible but given the bizarre nature of the novel, they are easily accepted and while the novel, on the back cover, is billed as a “masterpiece of postmodern literary parody” the only postmodernism I sensed was the slight feeling that whatever they did with their lives, Monzó was still the puppet master:

Anna-Francesca woke up screaming…she couldn’t remember what she’d been dreaming about…she didn’t like being at the mercy of something over which she had so little control.

For all its comic invention and ponderings of humanity, I was never immersed in The Enormity Of The Tragedy and found myself dipping in and out rather than avidly devouring it. Perhaps that was Monzó’s intention, as I felt like one of the characters within, never able to truly connect – them with each other, me with the book. Sex is the nearest they ever come (I didn’t even get that far with the book!) and, as time draws near for Ramon-Maria, he comes to realise that a life with so much material pleasure is still one wasted.

No doubt the novel is funnier in its original Catalan and I can’t help feel that the translation is, while mostly enjoyable, somewhat lacking. I never really felt the humour (but that may just be my sense of fun versus Monzó’s) and there were typographical errors that popped up from time to time. Monzó’s narrative sidetracks can be amusing although one – where Anna-Francesca learns all the ways to kill someone – felt far too long. And I was sometimes confused because every characters has a double-barrelled name, many of them being Maria-This or That-Maria.

Being limited to The Enormity of Tragedy as a way to introduce myself to Quim Monzó, I suppose the novel is as good a way as any. It’s entertaining and its idiosyncrasies are, for the most part, charming. Insignificant events segue into rambling tangents and astute observations on people and their relationships, despite its own characters being a cast of grotesques. But as a parody – of what? – I’m less convinced and, as I see it, for what is an otherwise enjoyable novel the biggest tragedy is that of the comedy.

Great title – shame the book didn’t quite live up to it. I doubt I would find the book half as entertaining as your review – so I’ll give this one a miss. I’m still giggling at your opening sentence though!!!

Often humour doesn’t transport well across different nations, let alone languages. From your quotes, it looks badly translated (but then that’s just my opinion… I’m judging it against a book I read recently, Mr Muo’s Travelling Couch by Dai Sijie, translated wonderfully into English from French (are we allowed to mention).

Quim = keem? I don’t get it.

steffee, quim is slang for female genitalia.

Gosh, really? I know it says its origin is unclear, but why?

Looking around, one possibility is Cwm, the Welsh for valley.

And here I was thinking I couldn’t possibly appear any more foolish.

But cwm is pronounced cum. And cwm is celtic based, whilst quim is clearly latin based? Interesting, still.

Ah well, looking around further there’s the Portuguese quente, meaning warm. That’s Latin, at least, and should meet your criteria. I doubt I’ll be losing much sleep over it. 😉

Si, aber tengo une petite Besessenheit con las lenguas.

Diolch (the only word I have managed to learn in 3 months of living in Wales – oh, apart from those on road signs, and Prifysgol, obviously…).

Warm though? Cute.