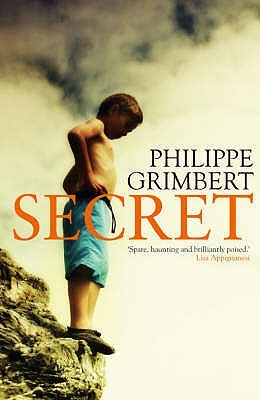

On my regular visits to book shops there has been one book that I’ve picked up on each visit, pondered it awhile, and returned to the shelves. Not because it didn’t interest me, but because other books I picked up interested me more. However, having seen a positive review elsewhere, I decided that the next time I picked it up I wouldn’t put it down until I’d read it. So, it came to be that I read Secret (2004), by Philippe Grimbert, winner of notable French literary prizes. And besides, it’s always fun to be part of a secret.

Grimbert is by trade a psychoanalyst and it appears that for his second novel he has decided to sit himself on the couch and delve into his own family history, providing a semi-autobiographical account of growing up in post-war France. Fiction and reality are almost inseparable here as the narrator is Grimbert himself and the events are real. Secret, then, is an attempt by the author to flesh out his family history prior to his own birth, in which an unearthed secret is hidden.

Of athletic parents, Grimbert is a child of “thinness and sickly pallor”, and begins by talking of how he invented an imaginary brother, someone older and stronger, someone he’d never become, a brother “who would burden [him] with the full force of his weight”, to fill the hole in his world:

I always felt envious when I went to stay with a friend and a similar-looking boy walked in. The same dishevelled hair and lopsided grin would be introduced with two words: ‘My brother’. An enigma, this intruder with whom everything must be shared, even love. A real brother. Someone in whose face you discovered like features: a persistently straying lock of hair, a pointy tooth… A room-mate of whom you knew the most intimate things: moods, tastes, weaknesses, smell. Exotic for me who reigned alone over the empire of my family’s four room flat.

What follows then is the realisation that buried deep in his mind, the imaginary brother has his roots in a half-brother who died before Philippe was born. The novel proceeds to tell a version of Grimbert’s family history, imagined from the bones of what he knows:

For a long time I was a young boy who dreamed of having a perfect family. I used the rare glimpses they gave me to build a picture of how my parents had met. A few incidental words about their childhood, snippets of information about their youth, their love… I pounced on these fragments to create my unlikely tale. In my own way I unwound the tangle of their lives and, much as I had invented myself a brother, created from scratch the meeting of the two bodies from which I was born, as if I were writing a novel.

By doing this he learns how his father’s first marriage spawned the half-brother, despite having always had eyes for the woman who became Grimbert’s mother. But it goes deeper than that, for after his fifteenth birthday Philippe learns “what [he] had always known”: that his past is Jewish. His father, by deed poll, had changed their name from Grinberg to Grimbert, thus allowing him to “plant roots deep in French soil.” Confronted on the truth he replies that “we’ve always had that name”. And so the true nature of the Grimbert history comes to light as the author imagines what it would have been like to live in occupied France, as a Jew:

The yellow stain distinguished them to others but also allowed them to recognise each other, binding together a community that, because it was hiding itself, had sometimes not realised its own existence.

So it continues that Grimbert pieces together his family history during and after the war, taking what is known and supposing the rest, finding in his fictions reasons for why events happened as they did. And as the author works through the memory of his characters, the great secret that lies at the heart of the family is aired and the burden they represent cast aside, leading to final tragic circumstances.

Grimbert’s prose is terse, mildy poetic at times, and, along with its notion of imagining one’s family’s past, is reminiscent of Anne Enright’s The Gathering, only more optimistic, interesting, and enjoyable. At no point does the author brood on the past, each short section being a delicate meditation or revelation, culminating in the harrowing aftermath of one family’s life during wartime that is ultimately poignant in the telling. In sharing the secret of his brother Grimbert no longer needs to invent, for with the secret aired he is no longer alone.

Secret is published as Memory in the US.

Now this is exactly what I would have written, if I could.

I so agree with you about the lack of brooding in what so easily could have been a tale of bitterness and resentment.

Great book, great review.

Thanks, Eve. For your words, and for encouraging me to finally make the decision to buy it.

Ooh, saw this in Waterstone’s a couple of times recently and didn’t quite make the decision to buy. Bloggers’ synchronicity??

Ooh, I really like the sound of this. And so the TBR pile lengthens. 🙂

It is a beautifully written, lyrical book about a family and the turbulent nature of world events and the cost to human relationships.

My tears flowed upon reading it.

I highly recommend it.

Really? I don’t think I could cry on reading a book. I’m probably more likely to sit with some solemn reflection. Still, at least you have tears at something substantial, unlike all those who say they cried at tosh like The Kite Runner.

I just purchased Secret only to find I had already bought and read Memory…the exact same book with a different title! What gives?

Publishers have no shame in changing titles to try and maximise a book’s chances in a particular market.