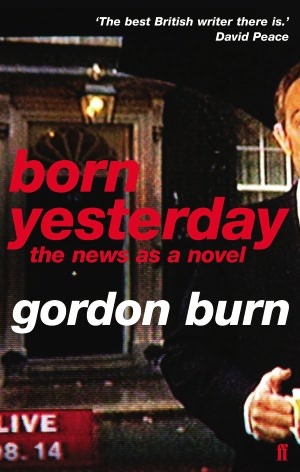

Having had the experience of reading Gordon Burn’s fiction – Fullalove, a novel about a hack journalist intruding on the bereaved to get a story – and his non-fiction – Best And Edwards, a literary account of the lightning quick and slow burn deaths of Duncan Edwards and George Best – and favouring the latter, it now seems Burn is intent on blurring the lines between both as his new book, Born Yesterday: The News As A Novel (2008), is exactly as the subtitle implies: the news…as a novel.

It’s a strange conceit, taking real life events and making a fiction of them, but in a roundabout way that’s exactly what happens everyday in the newspapers, on television, on radio. So here, with “the curiously intimate knowledge the world garners about an unknown figure” Burn, with himself as narrator, finds himself obsessing over important news stories and reporting back not the truth, but what susbtitutes for truth these days.

The news. Always something – usually unpleasant – happening far away to a stranger; to somebody else, somewhere that we’re lucky not to be.

The news, in this case, is predominantly focused around July 2007, in which Britain underwent “a summer of disappearances, absences, some voluntary, others not” and its cast of characters should be recognisable to anyone who followed the larger news stories of the year: Kate and Gerry McCann, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, John Smeaton, and Kate Middleton. Add to these the stories of floods, foot-and-mouth outbreaks, and meaningless stabbings and shootings and it shows the bleak landscape of a year fresh in the memory.

As is common in Burn’s work he turns his attention to the notion of celebrity and works with Warhol’s dictum that everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes. And the fifteen minutes of many characters here come by horrific circumstances.

With John Smeaton (“working-class, Scottish, plain-talking man of the people”) it’s the terrorist attack on Glasgow airport and his taking the fight to a flailing terrorist that elevates him in the public eye, first as a media sensation, then political pawn:

By his second visit to number 10 in October, SuperSmeato was wishing he could just stay at home with his Xbox for a week. Have a few nights in his own bed. Even better, he would be up in the north of Scotland, fly-fishing. His mobile would be back at home, switched off, and nobody would know where he was.

In opposition to Smeaton’s media rise, there’s the tale of the McCanns, Kate and Gerry (“controlled, collected, articulate, focused”) who sought to use the media to help find their missing daughter, Madeleine, only to find themselves, because of the way the presented themselves, turned against:

‘We’re normal people,’ Kate McCann protested when her family’s transition from being unknown to well known, and the perks that come with the transition – a hotline to senior members of the government, for example – were just starting to raise resentments: the first signs of a backlash were beginning to become apparent in eruptions of public volatility and paranoia.

The largest news story running through Born Yesterday, however, is the handover of office from Tony Blair (“One minute [he] was part of the national static, and the next he was gone.”) to his Chancellor, Gordon Brown (“an analogue politician in a digital age”). Where the Blair government was much like the media in spinning on the truth to its own ends, always presenting an optimistic mask, Brown’s tenure started differently:

The crises that piled up around Gordon Brown in his first weeks of office – the attempted terrorist attacks on London and Glasgow, the summer floods in the midlands and the north, foot-and-mouth: fire, flood and pestilence, a marvellous start for a son of the manse, as a number of people pointed out – these gifts from the gods required him to be thunder-faced, decisive, dogged, statesmanlike. The one thing they didn’t require him to do was the thing he had always had a problem with: they didn’t require him to smile.

As narrator, Burn is regularly out and about, and in the opening scene is walking through a park sometimes frequented by Margaret Thatcher and it’s here that we get the first sense of the novel’s purpose:

In office, Mrs Thatcher never read newspapers. She only read what her press secretary Bernard Ingham told her was in them. Out of office, though, the rumour mill insists she has all the papers brought to her every morning, when she sets about them with a marker pen, highlighting idiocies, striking through innaccuracies, furiously scribbling comments and corrections in the margin.

One can only assume that Burn himself echoed this action, working his way through the news of 2007 to produce Born Yesterday and instead of making corrections, made connections. For while it ultimately means nothing, he can’t help but linger on the fact that Gordon Brown, Madeleine McCann, and the first suspect in her disappearance, Robert Murat, all have problems with their eyes; or that Gerry, Kate, and the terrorists in Glasgow and London were all, to some extent, involved in the medical profession. In getting behind these connections, Burn offers up musings that add depth to what we get from newspapers, television, and radio:

It is often said that today’s abundance of media images create a screen between the individual and the world, and that this is the source of the feeling we all increasingly have of seeing everything but of being able to do nothing. The media gives us images of everything – but only images.

Despite how high profile the stories recounted in Born Yesterday are, they still make for compelling reading in the way, Burn as prose stylist, evokes the misery of somehow being involved. Sometimes it can venture into duller territory, when providing backstory, but overall its a interesting work, full of memorable characters, literary references, and an excellent eye for detail. By giving an account of exactly what was going on in 2007, it must surely be the definitive state-of-the-nation novel.

I’m saddened to discover that Gordon Burn recently passed away, aged 61, from cancer. (via Guardian)