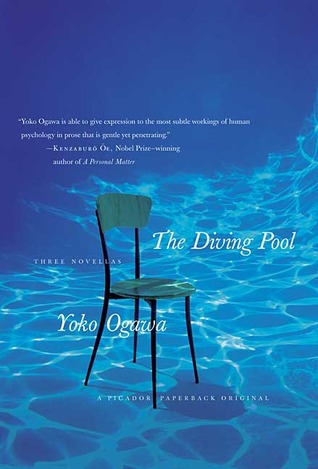

According to the inside flap Yoko Agawa has written more than twenty books and won every major Japanese literary award. Where else is there for her to go? Either it’s scooping every minor Japanese literary award – probably not worth her while – or it’s off to international waters, to a brand new audience, and perhaps add to her trophy case with an IMPAC, or something.

The Diving Pool, her first book translated to English, is not a novel but a collection of three novellas from early in her career, of about fifty pages, loosely connected by their content. All three are told by young women with a skewed outlook on reality relating stories about family members. In each, Ogawa deploys an precise style that maintains an eerie distance between the narrator and event, her words clinical and charged with meaning, always leading with a slow build that concludes with a twist – although backstroke is probably more apt.

Aya, the narrator of the title novella, lives with her parents in the Light House, which, she says, “is an orphanage where I am the only child who is not an orphan, a fact that has disfigured my family.” She has a crush on her foster-brother, who spends a great deal of time at the school pool honing his dive seemingly unaware that she is hiding in the bleachers (“I alone can see him, and he comes straight to me.”) admiring him from afar:

Does Jun let his body float free at the bottom of the pool, like a fetus in its mother’s womb. How I’d love to watch him to my heart’s content as he drifts there, utterly free.

It’s a frustrating thing, unrequited love, never mind being treated equal to the orphans by her parents, and Aya finds herself using one of the other orphans, a toddler named Rie, as an outlet:

When we grow up, we find ways to hide our anxieties, our loneliness, our fear and sorrow. But children hide nothing, putting everything into their tears, which they spread liberally about for the whole world to see. I wanted to savor every one of Rie’s tears, to run my tongue over the damp, festering, vulnerable places in her heart and open the wounds even wider.

The tone throughout is a haunting and detached, maintaining a clinical calm not unlike the pool before Jun makes his dive. Ogawa’s words, spare as they are, are carefully picked and shot through with meaning, so much so that it’s not hard to interpret Aya’s home as being a metaphor for people, also like a pool, where we can only question at what happens under the surface:

The church and the Light House are old, Western-style wooden buildings, their age apparent in every floorboard, hinge and tile. The structures have become quite complex through frequent additions, and from the outside it is impossible to grasp their layout. Inside, they are more confusing still, with long winding halls and small flights of stairs.

The Diving Pool, where each page drips with mentions of water, is a powerful story, the most powerful of the three contained in the collection, and the splash of its ending proves an excellent introduction to Ogawa as the dangers of living in the Light House become apparent, of standing solitary and staring off at one point with a single beam, oblivious to everything else around.

The other two novellas maintain the icy tone, with the epistolary Pregnancy Diary, in which a woman keeps a record of her sister’s pregnancy, annoyed that her sister seems to disregard the child growing within her (“The baby haunted the shadows that fell between us.”) and the more straightforward, yet downright creepy, Dormitory, in which a woman haunted by a sound from her past secures a room for her cousin at her old dorm, now in a state of decline, and finds herself caring for the manager, a man who has lost both arms and a leg.

It’s a pity that the novellas are presented in this order, as the prose of Dormitory is paciest and would have served as a better lead in to Ogawa’s cool, calculated style, and would certainly have made the impact of The Diving Pool much stronger, where the satisfactory snapping shut of the book would have left waves rather than ripples. But there’s much to appreciate here, and that Ogawa has a back catalogue ripe for translation, is reason enough to dive in, even if these three novellas are the shallow end.

I’m going to look out for this when it’s published. The whole subtle idea of ‘wrong’, or even cruel, emotions in the context of ordinary people and their ordinary relationships, is strangely appealing. It’s nice to feel unsettled, once in a while.

steffee, it is published. It was released at the start of this month.

Ah… I did search and saw 2008 and just assumed it wouldn’t be yet. Duh!

I’m going to look out for this when it’s published. The whole subtle idea of ‘wrong’, or even cruel, emotions in the context of ordinary people and their ordinary relationships, is strangely appealing. It’s nice to feel unsettled, once in a while.