When the Booker longlist was announced late last month, I don’t think there was anyone who would have expected to see Tom Rob Smith’s Child 44 make the cut, including Smith himself. It no doubt surprised many that the publisher even had the gall to submit it. Why? Because it’s a thriller and, with the old snobbery hat on, thrillers don’t belong in the Booker. However, that’s a straight out lie, since thrillers have been in the running before, but usually by writers for whom such books are not the only string to their bow. But, as Oscar Wilde said, books are either well written or badly written, and that is all. So which is Child 44?

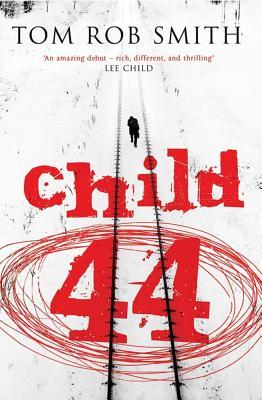

A portentous cover, featuring praise limited to those also treading the crime genre, such as Lee Child and Nelson DeMille, rings alarm bells. Likewise an encomium from a screenwriter who, from his snippet, can’t seem to see past the action. And in reading Child 44, it’s no surprise to find that Tom Rob Smith is also a screenwriter.

The novel reads like a film and, as it turns out, it started life as a treatment but became a novel at the advice of Smith’s film agent. Sadly, it maintains the shallow depth of a script – dialogue, some scene setting – as Smith has written it with an eye – if not both – squarely on a big budget, big screen outing.

Opening with a scene in Ukraine in 1933, where a couple of young boys hunt for a cat to alleviate the starvation that has gripped the nation, the story then fast fowards twenty years and introduces us to Leo Demidov, war hero and officer in the Ministry of State Security. Demidov is tasked with relaying to the grieving family of a young boy, found mutiltated by a railway lin, that the death was accidental. In this, Smith introduces us to the central conceit of his setting: there is no crime.

“Few people believed this absolutely. There were blemishes: this was a society still in transition, not perfect yet. As an MGB officer it was Leo’s duty to study the works of Lenin, in fact it was every citizen’s duty. He knew that social excesses – crime – would wither away as poverty and want disappeared. They hadn’t reached that plateau yet. Things were stolen, drunken disputes became violent: there were the urki – the criminal gangs. But people had to believe that they were moving to a better state of existence. To call this murder was to take a giant step backwards.

Of course, it’s definitely murder most foul, although similar incidents are treated as isolated ones, with innocents being tried and executed to cover up the fact that Russia has a serial killer in its midst. While it opens with an interesting idea, of a man conflicted between adherence to state doctrine and what his own eyes tell him, these first two hundred plus pages – the events of which are are spelled out in the inside cover – are more a set up for what is to come, namely standard action fare.

It’s a treasure trove of nonsense that leads to the most risible modus operandi put in print. But in getting there, there’s much more to cringe at. Smith has chosen a pointless quirk of representing all dialogue in italics; his research rarely extends beyond a sprinkling of Russian words, each immediately explained; he has trouble maintaining viewpoint, sometimes even within a paragraph; and, most foul, he tells everything. Not at one point do you ever infer something – there’s no imagination required.

Smith bumbles in and out of characters heads, revealing their every thought (where action would be better suited) and it leaves the reader breathless with the book in hand wondering where they come into it. And that’s entertainment? Child 44, I think, is two novels in one, each extremely underdone: the potential conflict study of self and State, and the run of the mill thriller. I suspect Smith intended the latter, and could easily have done away with the first half of the book. But he’s a man who likes to pad out with scenes that would look good on screen, even if they serve nothing on the page.

Without the Booker I would never have read Child 44, and that’s what is most annoying about the book: that is a throwaway entertainment that fails to entertain. We can only guess as to the sanity of the Booker panel in selecting this book. But for a thriller that is supposed to have numerous shocking twists and turns, the biggest shock is that something with so much padding could still leave me so cold.

A good book to give to Oxfam.

Sorry to hear that it was a waste of time.

Gah, no! I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. Plus, the library wouldn’t like me doing that.

I don’t think of it as a waste of time. More a confirmation of why I grew out of these sort of books years okay.

Thanks for this. I’m working my way through as many of the long list as I can, can’t possibly get through them all before short listing, so won’t even go looking for this. At the moment I’m really enjoying ‘Sea of Poppies’. Have you read that?

Not yet, Ann. I’m halfway through The Clothes On Their Backs and have read Netherland. Sea Of Poppies is next on the list.

Thanks, Stewart. What were the Booker folks thinking? I read another review that was similar to yours; nothing left to the imagination, and a nonsensical plot. Also, the dialogue is in italics? Good God!

Yes, Smith has apparently said it was to demonstrate that his characters weren’t speaking English. How thick is his audience? Do they really think that this cast of Russians will be going around talking in a decadent western lingo? At least they think in English, since internalising isn’t italicised. Here’s the actual qwote from the interview:

No, it doesn’t read easier, because it draws attention to it. Yes, it is empty experimentalism.

To say that I liked the book more than you, is not to say much. I think it’s an fair book to read on an airplane. The kind of thing you won’t mind leaving in the back of the seat in front of you when you arrive.

The fact that is has a Booker nomination does not speak well for the future of the award. Are we to continue taking the Booker seriously? I eagerly await the short list, which is probably the point.

CB, I can’t say I’ve ever understood the concept of airplane novels. Many books do offer some light entertainment, but I don’t think Child 44 can be such a thing as that would be giving it special dispensation for being technically inept. I think we should expect novels, light fare or otherwise, to be good at what they do, and this book fails because Smith isn’t up to the job of entertaining. We can’t turn away from the fact that the words play a key role in many aspects. and a misuuse of these just ruins any possible fun to be had.

I can, however, see the differences in our approaches, with you reading it before it got elavated to a level that pretty much puts greater expectations behind it. I wouldn’t have read it prior to the longlist, and can only look on with an exclamation mark over my head as to what the judging panel were thinking.

I agree with Stewart that being light entertainment is no excuse for technical ineptitude. A book should not be criticised for not being what it does not set out to be, but it can and should be criticised for not being what it does set out to be.

To criticise a piece of literary fiction for its lack of tight plotting or its failure to engage with the impact of technology on society will generally be rather to miss the point. Similarly, criticising a thriller for sketchy characterisation or lack of internal character growth I think would miss the point a bit. But there’s plenty you still can fairly criticise on.

Does it persuade? Is the pacing tight? Is the prose punchy and exciting? Is the dialogue credible? Do you care about the protagonist (irrelevant to most fiction, I would argue deeply relevant to the thriller genre as a rule)? Is the use of language intrusive? Are the twists unexpected yet satisfying? Does it break suspension of disbelief too severely? That’s just off the top of my head. If I were a fan of the genre, I’m sure I’d come up with more.

It is possible to critique a thriller on its own terms and ask “if this is intended as light entertainment, is it good light entertainment?” And since there’s plenty of good light entertainment around, if one is looking for an airplane novel there are good and bad examples of that just as there are of everything else.

Of course, we don’t now have the benefit that CB had of reading this without the weight of expectations it now carries, the main effect of which is to bring it to the attention of people who would otherwise not have dreamt of reading it.

It does seem something has gone a bit astray with the judging process this year, which is a shame and which makes me glad I wait until books are in paperback before reading them and so am not yet reading any of this year’s entries (and at this rate, query if I ever will read any of them).

In my defense, I never said it was a good airplane book, just a fair one. I rank good above fair, probably a 3 on a scale of 5.

I’ve sense tried two of the more literary works on the long list and I’d have to rank them in the fair range also. Maybe it was just a bad year.

Once again, I think the debate on Child 44 throws up the perennial interesting point: what makes “good” literature? Or, more specifically, can a book marketed as genre fiction, be considered “serious” or “literary.” Increasingly, I find such terms (and pigeonholes) redundant for fiction. I for one enjoyed the book immensely. Yes, it had (many) flaws, but I found it a riveting read (and I never read crime fiction!). And in the end, that is all it purported to be. Personally, I find other novels that promise so much more (Northern Clemency for one)and fail to deliver time and time again infintely more frustrating. And in any case, why should the fact this was selected for Booker List warrant such keen examination (and then dismissal)? The Booker list has been full of duds in recent years, so perhaps we shouldn’t expect too much…

I think it can. I don’t think we can consider Child 44 as either serious or literary though. (Which brings us round to that old chicken and egg scenario of what is literary anyway?)

Oh, I agree with you there Nige. I could quite happily see all the fiction genres of a book store assimilated into one giant A to Z.

Because the Booker is a literary prize – not some crime dagger award – and those in conention for it should be among the best, in the judges’ collective opinion, that the Commonwealth has to offer for that particular year. Child 44, with all its flaws, idiosyncrasies, and whatnot is simply not good enough – by my standards, anyway, since that’s all I’ve got to measure it against – to be considered the best of the year. (Okay, so I need to read more from the year in question.)