After a lengthy hiatus from reading, I thought it best to reaquaint myself to books with something pacy that would have the pages turning themselves with gleeful abandon. A thriller, then. The only issue I have with many of the thrillers I’ve sampled over the years is that the writer is never any good. Yes, they sell loads, but their style hovers at such a surface level what counts for characterisation appears to be the colour of a person’s hair and how many pounds they weigh.

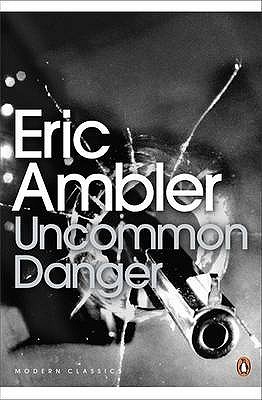

Marking his centenery, the recent reissue of Eric Ambler’s early spy novels has come at just the right time and solved my predicament. What’s more, I don’t know how long they’ve been out of print, but they have returned with what I consider one of the highest forms of recommendation: being a Penguin Modern Classic. Graham Greene considered Ambler “our best thriller writer” and Alfred Hitchcock was also a fan. All this in mind, I turned to Uncommon Danger (1937), Ambler’s second novel – also his first serious thriller.

At the heart of the novel is the misadventures of Kenton, a British journalist working overseas, who has recently had the misfortune of losing money playing poker-dice and landed himself in debt. When he’s introduced he is boarding a train from Germany to Austria so as to visit an old Jewish friend, who he once helped leave Munich a few years before, in the hope of borrowing money to pay off said debt. However, while travelling, another passenger offers him the chance to earn some cash by taking some securities across the border:

At that moment Kenton ceased for a time to be an impartial recorder of events and became a participator. Three hundred marks! A hundred owing to the Havas man left two hundred. Two hundred! Enough to get back to Berlin with plenty to spare. Brown-Eyes might be anything but what he claimed, and he, Kenton, might be heading straight for a German prison, but it was worth the risk – for three hundred marks.

It goes without saying that the high fee and the dodgy request invites trouble, and where Uncommon Danger picks up points is in its use of a character like Kenton. With a spy novel the expectation is there that the main character will be an agent of one side going up against the forces of the enemy – and Ian Fleming‘s lifeless Bond novels spring to mind here – but this it-could-happen-to-anyone approach to international espionage works well to bring us into a murky underworld where, away from the security of governments and friendly agents, the predicament becomes truly a frightening prospect, for anyone can stumble into it.

The situation that Kenton stumbles into is a plot to install a Fascist government in Romania, an intention outlined in an opening prologue that shows a board meeting of the Pan-Eurasian Petroleum Company in London as they conspire to gain access to the country’s oilfields. Of course, men in boardrooms tend not to involve themselves explicitly, as is explained later in the novel:

‘You see, your business man desires the end, but dislikes the means. He likes an easy conscience. He likes to sit in his office and deal honestly with other business men. That is why Saridza is necessary. For at some point or other in the amazingly complicated business structure of the world, there is always dirty work to be done.

It would be unfair to label Saridza as the villain of the piece, as the world Ambler writes about is never so black and white. He is, however, the agent of his conspiring paymasters and is seen throughout Uncommon Danger doing their dirty work. One such task is retrieving the aforementioned securities from Kenton, something which, given that he’s not a part of the over arching plot, should easy enough. In situations like this, however, Ambler shows he can add some dimension to his characters in that they dictate the novel’s plot rather than blindly adhere to any preconceived storyline:

Kenton hesitated. His first impulse was to give the man the information he wanted and get out of the place. He glanced at the two men. […] In their eyes, watching him intently, there was a hint of amused expectation. Then, rather to his surprise, he became conscious of a new and unfamiliar sensation. For the first time in his adult life someone was trying to coerce him with threats into making a decision, and his mind was reacting with cold, angry, obstinate refusal.

Kenton’s hot-headedness leads him back and forth through a landscape of thrills, continuously moving across borders and between the arms of Saridza and a cell of Russian agents keen on preventing the Fascist plot. The only time the pace lets up is when Ambler opts to let his characters talk, at length, about the geo-political landscape –

‘Until nineteen thirty-six,’ he said, ‘Roumania could be summed up politically in one word – Titulescu. Titulesco’s foreign policy was based on friendship with Soviet Russia. The Little Entente was the first link in the chain round Germany. The last link was the Franco-Soviet pact. But there is reaction in the air of Roumania as there is in every other European country. With Fascism in Italy, National-Socialism in Germany, the Croix de Feu in France, Rexism in Belgium, and Nationalism in Spain, it was hardly likely that Roumania would escape the contagion.’

– a technique that would typically be unforgivable just for the sheer clunky way of forcing exposition into the story, but which helps here, perhaps because it talks of an interwar period with a Europe long since altered and inconceivable today.

In writing Uncommon Danger, Ambler has certainly challenged my concerns over spy novels. His characters are full-blooded enough to be believed, without ever being larger-than-life, and his casting of big business at the heart of the novel takes the focus away from espionage between nation states with agents defecting all over the shop. The prose may not be anything to sing the praises of, it’s all about the pace here, but it feels real, and this being only Ambler’s first serious thriller, he hits the ground running. Fitting, really, for an entertaining little thriller.

Ambler is one of my favorites. I’m glad to see he’s being reissued. I’ve not read this one yet, but I’ll look for it. I can’t comment on his prose in this book, but I would like to defend him a bit. With spy novels and thrillers the prose exists to serve the plot which is one thing that marks the genre. To this end, I think Ambler’s prose is quite good, generally spare and very much to the point. He evokes time and place well and creates an atmospheric tension that suits coldwar era spy novels well. He derserves to be much better known.

CB, you could always use The Book Depository to get a copy of it, free delivery worldwide, and all that.

I don’t think you need to defend Ambler. There’s an early mention that Kenton isn’t one for scenery, so there isn’t much. The prose does indeed drive one on through the book and the only time I was forced to stop was to take in the historical/political machinations of pre-war Europe that, as I said, were delivered in lengthy patches of dialogue. Other than that, reading it was a breeze and, while not showy, the prose proved effective for rarely was I pulled from the narrative to question a phrasing. Truth be told, I was tempted last night to get cracking on the next Ambler novel I have, Epitaph For A Spy.

Well, if Hitchcock was a fan…

Sometimes a racy, fast paced plot is desirable. The geo-politics sounds interesting, also.

My Dad loves Eric Ambler, but I had discounted him for not being Bond! I must rectify that.

Annabel, I think it’s the whole Bond or, generically, the secret agent thing that puts me off. The genre, perhaps somewhat erroneously, often gives off vibes of a world where everyone is out to double/triple cross each other for the sake of governmental power. (That said, I have little issue with spy movies, so it’s likely to be the quality of the prose.)

I’m glad Ambler has done something to break me away from such preconceptions, and I feel encouraged to read some others, like John le Carre and Alan Furst, to see what they have to offer.

I’m glad you mentioned LeCarre, Stewart, because I have been thinking about him ever since this post went up. While I have not admitted it except to close friends before, he is someone whose books I turn to when I want an old-fashioned make me think at 50 per cent read (anything less and the mind wanders, but there are times when I don’t want more). I usually don’t get to him until a couple of years after the books appears but I think I have read all but the last two (I don’t really follow his catalogue) and most have been read more than once.

An interesting review Stewart, and good to have you back. I’ll likely pick this one up, I’d heard of Ambler but never got round to him.

I have a Furst written up on my blog if you’re interested, The Polish Officer, it’s the second of his I read and I actually preferred the other (Dark Star), but it may still be of interest to you.

Also, today the Guardian has a piece on Ambler here: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/jun/06/eric-ambler-mask-dimitrios-journey-fear which I have yet to read but do plan to.

I actually rather like Le Carre Kevin, he’s lousy with female characterisation I think but otherwise pretty good, Len Deighton is also worth a look in this vein – his stuff is the antithesis of Fleming’s (which is good, as I don’t personally rate Fleming much).

I also agree on le Carré, based on the two books of his I’ve read (Absolute Friends and The Constant Gardener) – I’m no fan of spy novels per se but I do think he’s a good writer. I’m sure some of his more well known books are even better.

Also, I’ve just begun Eric Ambler’s Journey into Fear. Penguin issued this one as a limited edition proof before publication, so I’m extrapolating from that that it may be the one they see as his best book. I’m only a few pages in but will report my thoughts in due course, and then those interested will have my and Stewart’s opinions against which to triangulate their own.

Now that’s someone who’s worthy of a revival. I’ve not read an Amble book for years and it was great to be reminded of him.

The aforementioned Alan Furst picks his top five spy novels and Eric Ambler’s The Levanter is on the list.

Re: Le Carre: I re-read The Spy Who Came in from the Cold fairly recently, for the first time in 20 years, and felt it had not aged well. Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, on the other hand, I have re-read twice in the past ten years and it is first-rate. Essentially it’s a fictive re-telling of the Cambridge spy ring, but it’s also a condition-of-England novel; it has a resonance far beyond its subject matter. I still think it has the best opening chapter I’ve ever read.

It’s very good to see that Eric Ambler has been given a push; the Vintage Crime Black Library in the US has kept some of his titles in print, but until the PMC reprints, only The Levanter and The Light of Day (filmed as Topkapi) were available in the UK, courtesy of No Exit Press.