A.L. Kennedy is one of Scotland’s greatest contemporary writers who, over the last twenty years, has produced a body of work spanning novels, short stories, non-fiction, screenplays, and more. In recent years she’s been a regular feature in comedy clubs, something which polarised opinion at the start, and since 2007 her stock has risen with a string of prizes and awards, including the Best Book at the Costa Awards (for fifth novel, Day) and the Austrian State Prize for Literary Fiction, putting her amongst distinguished names like Umberto Eco, Salman Rushdie, and Milan Kundera, not to mention two recent British Nobel laureates.

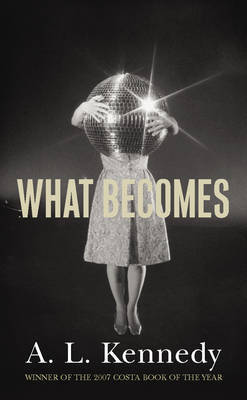

Other than a few short stories from her first collection, I’ve read little of Kennedy, owing to an increasing preference for world literature over what’s on my doorstep. Recently I’ve felt the need to survey home soil writers, and so it is that I read What Becomes (2009), a new short story collection, her fifth to date.

The collection is named for the opening story which opens with Frank taking his seat in a small, empty cinema and waiting for the movie to start. In the prolonged time it takes to gear up, he finds his mind wandering to recent events, to one night in particular that accelerated the fall of an already splintered marriage. As he prepares a soup, slices some squash, he accidentally cuts his finger and here Kennedy provides us with a fantastic piece of subtle foreshadowing, noting that “he hadn’t been paying attention and so he got what he deserved” and, later, when the denouement comes, the echo of “funny how he didn’t feel the pain until he saw the wound” assumes a satisfying symbolic power.

Frank’s a detective, a catalyst in his failing marriage, for his mind deals with things differently than his wife (“she’d never known the rooms he’d seen…”) and communication between them is strained. While they share the grief underlying the story, each handles it in their own way. She fails to realise he’s hurting, while he retreats inside, forensically trying to overcome the insurmountable.

Invisible rooms – that’s what he made – he’d think and think until everything disappeared beyond what he needed: signs of intention, direction, position: the nakedness of wrong: who stood where, did what, how often, how fast, how hard, how ultimately completely without hope – what exactly became of them.

This sets the stage for what’s to come. The title recalls the old song that asks what becomes of the brokenhearted, and in the twelve stories that make up What Becomes, Kennedy sets out to examine scenes of hopelessness and heartbreak that are at times funny, other times uplifting, yet always underscored with melancholy.

In Edinburgh we meet Peter, a greengrocer, who finds his passions aroused when a younger woman starts hovering around his shop, more for him than his wares. And when he offers her some apples, saying, ‘They’re fine to eat, they’ll be fine for days. But everything’s going off in the end, isn’t it?’, Kennedy once again shows her flair for foreshadowing and picking the precise symbol that reinforces the effect of the overall story. Similarly, in Whole Family With Young Children Devasted, the title appears on a poster about a missing cat, but it readily applies to the wider issues of the story.

The telling of the stories is varied, Kennedy seemingly happy in first and third person modes, and getting into the heads of men and women. There’s also some mild experimentation, where Sympathy, about a woman having sex with a stranger in a hotel room, is told entirely through dialogue.

‘…if we keep talking, we’re going to end up –‘

‘Getting to know each other?’

‘That wouldn’t work.’

‘Fine.’

Aside from the symbolic power of the stories, where the success is achieved is in Kennedy’s characters. Her understanding of them is second to none. As she describes their actions and feelings, their thoughts seem to take life of their own, interjecting, pondering, and reflecting on the hopeless situations that circumstance has dealt them. In Sympathy, which follows the death of a children’s entertainer (“Barry with the fake face for parties, Barry who loved to flirt”) who, like a fair number in this collection, was no stranger to an unhappy marriage. The child between is someone for his wife to love, “a consolation for his inability to love her”, a flesh and bones creation made without thinking.

Although, Lynne had been thinking: otherwise, she wouldn’t have stared at her husband as he first picked up his daughter, hefted her tenderly, gracefully, feelingly — so the nurses could not help but remember the scene, believe it — and she had thought — Got you. She’d seen his eyes: the wide, unfamiliar chill that was settling in them and she had thought — Got you. Fuck you. Deal with that.

A highlight of the stories is the humour that runs through the. As God Made Us, in which a group of British soldiers who met in hospital (“Hospital — great place to meet folk, get new mates.”) have their annual meetup, shows this in its dialogue, following the lads will be lads mentality that until the collection’s theme catches up with it in an explosive outburst. Other stories show a subtler, truer humour, such as in Vanish, where Paul finds himself sitting next to an annoying person in a theatre and experiences something we can laugh it, because it’s the way we may think ourselves:

It was ridiculous and unfair to imagine a person like Simon could unknowingly drain each remaining pleasure from those around him and leave them bereft. ‘Do you know his work? Amazing guy. I’ve seen every show.’ Even so, as Simon cast his hands about, shifted and stretched, Paul found himself taking great care that they didn’t touch, didn’t even brush shoulders, just to be sure that no draining could take place.

Returning to the title story, Frank ponders at one point the buttons on a personal music player, saying,

‘They’ve anticipated you’ll want to repeat one track, over and over, so those three or four minutes can stay, you can keep that time steady in your head, roll it back, fold it back. They know you’ll want that. I want that.’

It rings true for the stories in What Becomes and is perhaps a foreshadowing of the collection itself, for each story is a multi-layered affair that sheds its many skins with each reading. In its singular focus on the melancholy side of human nature, the whole is unified and it becomes a rounded work. And in those epiphanous moments where the stories show their cards, the revelations, through their believability, prove memorable. Kennedy knows you’ll want that. That’s what she delivers.

Poor Frank. Poor all of them. It sounds quite depressing. Although you say it has a mix of “melancholy”, “funny” and “uplifting”, it certainly sounds more the melancholy.

Nice review Stewart, I’ve been interested in trying Kennedy for a little while now, would you recommend this as a place to start?

That would be hard for me to say, Max, because, as I say above, other than a couple of short stories from her first collection, Night Geometry And The Garscadden Train, this book is all I’ve read. So it’s as good a place as any, I suppose.

With short story collections there’s always going to be ones you like and ones you don’t, unless some alchemy binds them all in brilliance, so you’re at least going to be partially satisfied. Not like a novel, where it’s a singular thing to be liked, disliked, or given a shrug of the shoulder, punctuated by a “meh!”

This is one I must read as I really enjoyed her novel Day. I’m also trying to read more short stories, so I’ve ordered this from the library. Did you hear her on R4’s PM programme last month as one of their spoof the people’s choice of speaker of the house of commons? She sounds like a great lady

Hope you like it, Tom. It’s not out until early August, so you may have a short wait from your library. Still, there’s four more collections available for now.

I didn’t hear her on Radio 4, but that’s only because I don’t listen to the radio at all, with the exception of I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue via BBC iPlayer.

Short stories are something I’m trying to find a better taste for. To that, I’ve got a bunch of collections waiting to be read. And I’m looking forward to them.

Thanks, I have a couple of Kennedys sitting on my shelf and this encourages me to get a move on.

I notice in the Guardian today AL Kennedy claims this book hasn’t officially been released yet, even though people seem to be able to buy it in shops.

Re: the Austrian State prize, it is strange how immensely respected AL Kennedy’s work seems to be in the German speaking world (releases of her novels seem to be events over there), while she’s (still) fairly ignored over her.

I saw that article. I suppose when shops get books in, it makes more sense for them to be getting cash in the till rather than sitting on them. To this effect I’ve picked up Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, the paperback of Philip Roth’s Indignation, and the reissue of Bohumil Hrabal’s Dancing Lessons For The Advaned In Age – all, along with the Kennedy, expect to hit shelves officially on the 6th August.

Jonathan Cape sent me this book back in June. It wasn’t even a proof. So they’ve been off the press for quite a bit of time; no wonder Kennedy has seen copies about ahead of ‘publication’ proper.