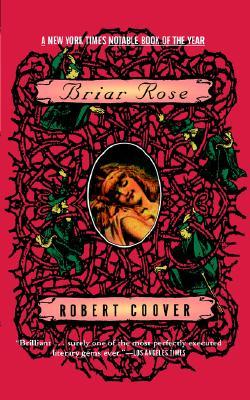

The American writer Robert Coover would appear to be a dot on the landscape of British literary consciousness – I don’t know how well known he is in the States – but a small number of his better known titles, such as The Public Burning, The Origin Of The Brunists, and short story collection, Pricksongs And Descants, have recently been appearing on the shelves of my local Waterstone’s. Curious to know more, but without immediately buying, I read about him online and found that he is a postmodernist of some repute and that his novel The Public Burning was the first major work of fiction to use still living people as characters (it was narrated by Richard Nixon). So, intrigued enough to wanting to sample Coover but not intrigued enough to get bogged down in a lengthy wedge of postmodern trickery, I opted for one of his novellas, Briar Rose (1996), a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and a reimagining of the Sleeping Beauty tale.

Although there are many variations on the Sleeping Beauty story, the common thread follows a girl on the cusp of adulthood forced to sleep for a hundred years after pricking her finger on a spindle, and who can only have the spell broken by a kiss. To this end Coover tells us the story from the point of view of three characters, told in alternating sections: Beauty, the handsome prince, and the evil fairy whose spindle is responsible for Beauty’s condition.

Briar Rose opens with the story of the prince on a quest to reach a castle after hearing rumours of a sleeping princess (“for all her hundred years and more, still a child, innocent and yielding. Achingly desirable. And desiring.”). What else can he do, as is the hero’s vocation, but race to her rescue? The castle has seen better times and a briar patch has grown around it, preventing easy access. Nevertheless, in an opening tinged with sexual imagery —

He is surprised to discover how easy it is. The branches part like thighs, the silky petals caress his cheeks. His drawn sword is stained, not with blood, but with dew and pollen. Yet another inflated legend. He has undertaken this great adventure, not for the supposed reward — what is another bedridden princess? — but in order to provoke a confrontation with the awful powers of enchantment itself. To tame mystery. To make, at last his name.

— the task is there to be undertaken, despite statements that he’d had been better off searching for the Golden Fleece or “another bloody grail”.Soon we are with Beauty, high in the castle where she sleeps her century’s sleep. But it’s not without a serious of recurring dreams “each forgotten in the very dreaming of them” although some elements produce an “ambient familiarity”. Her dreams see her wandering the castle, its myriad locations amorphous and unspecific, and longing for “the one”. And tucked away in these dreams is the evil fairy, her lone companion who regales her with tales of other sleeping princesses:

Whe she woke up— What was her name? What? The princess: What was her name? Oh, I don’t know, my child. Some called her Beauty, I think. That’s it, Sleeping Beauty. Have I heard this story before? Stop interrupting. When she woke up— How did she wake up? Did a prince kiss her? Ah. No. Well, not then.

Where fairy tales are prone to a form of Chinese whispers, so too do the evil fairy’s stories take on new forms and variations with each telling while remaining true to the original. In her ever forgetful dreams Beauty is ignorant that the stories are her story, albeit garnished, and Coover takes these fantastical tales – of incest, rape, ogres…and bears! – and injects a sense of real world logic into them —

Has that smug sleeper paused to consider how she will look and smell after a hundred years, lying comatose and untended in an unchanged bed? A century of collected menses alone should stagger the lustiest of princes.

— that, in turn, seems to influence the characters into becoming more logical themselves and begin to develop self-consciousness whereby they realise they are archetypes and struggle against it. The prince, for example, knowing that there isn’t a hero’s life once you are living happily ever after (“What is happily ever after, after all, but a fall into the ordinary, into human weakness, gathering despair, a fall into death?”) finds himself almost happy to be trapped in the increasingly aggressive briars (“he slashes, a branch falls; it grows back, doubly forked”).

The question is who’s mind are we in, if we are in anyone but the author’s mind? Is the princess in the castle a myth that drives the prince onward? Is the prince always, but never, coming to the rescue simply an instance of wishful thinking? The questions play back and forth with each other, placing us back with the prince at the start of the book: in a tangled briar of words that seem to part easily at first but eventually keep us rapt in their embrace.