Science fiction has been in the news a lot these days, most notably with Kim Stanley Robinson’s much publicised criticism about the lack of recognition awarded to the genre by judges of the Man Booker Prize (although it’s likely that sf publishers don’t submit the works for consideration). It’s a genre that seems to want to break away from being ghettoised and obtain respectability, to prove that it’s a genre of ideas rather than, as stereotypes imply, the domain of nerds.

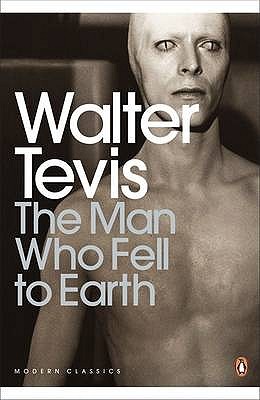

It’s not a genre that I would consciously gravitate to, put off as I am by the notion of space operas and many a sf cover, but I see no harm in sampling from time to time, although my preference would seem to go to those recognised as good examples of what science fiction is capable of, and it’s for this reason that I turned to Walter Tevis’ The Man Who Fell To Earth (1963). It’s probably better known for the film adaptation starring David Bowie but the original novel is an enjoyable journey in its own right.

The book opens in the year 1985 with our titular ‘man’ wandering around Kentucky and having his first experiences of interacting with human beings:

It was a woman, a tired-looking woman in a shapeless blue dress, shuffling towards him up the street. He quickly averted his eyes, dumbfounded. She did not look right. He had expected them to be about his size, but this one was more than a head shorter than he. Her complexion was ruddier than he had expected, and darker. And the look, the feel, was strange — even though he had known that seeing them would not be the same as watching them on television.

It is through television – and FM radio – that he has observed humanity before arriving on the planet from Anthea, his own world. To understand their ways helps in dealing with the “complex, long-prepared plan” he has come to effect. Said plan isn’t immediately explained but forms part of the novel’s mystery as we watch the rise of Thomas Jerome Newton (his assumed identity) from selling gold rings to small jeweller’s for lows sums to becoming a wealthy man by patenting and producing advanced technology for the market to consume under the umbrella of World Enterprises Corporation. The only hint as to what Newton needs the money for — his target amount is five hundred million dollars in five years — is in his answer to his patent lawyer, that it’s for a research project.

Being a novel set during the Cold War it’s no surprise that suspicion towards foreigners should feature in the novel, and with his meteoric rise in status, Newton begins to inspire the doubts of many people, notably Robert Bryce, a chemical engineer who, upon seeing one of the W.E. Corp’s new products – a self-developing camera film – concludes that it “It’s got to be a whole new technology…somebody digging up a science in the Mayan ruins…or from some other planet…” and burrows his way into Newton’s employ in order to sate his curiosity.

The relationship between Newton and Bryce is an interesting one as the initial suspicion over Newton’s true origins leads to an eventual friendship, and also allows us into Newton’s existential quandary. He’s a man alone in the world, different to everyone on the planet and losing his identity the more he lives as a human and yearns to out himself as an Anthean.

Then he spoke aloud, to himself, in English. ‘Who are you?’ he said. ‘And where do you belong?’

His own body stared back at him; but he could not recognize it as his own. It was alien, and frightening.

While the novel’s title could be read literally, about a man falling to Earth, the truer premise lies in Newton’s decline in purpose. From intentions to serve a masterplan his Anthean self begins to disintegrate under the gravity of human ways, accelerated by a certain closeness to his low status housekeeper, who introduced him to gin and taught him “that a huge and indifferent mass of persons had virtually no ambitions and no values whatever”, and the thought of his own people loses its importance:

…he, the Anthean, a superior being from a superior race, was losing control, becoming a degenerate, a drunkard, a lost and foolish creature, a renegade and, possibly, a traitor to his own.

Tevis’ prose isn’t particularly showy, he deals mostly in facts and details and drifts through the minds of his characters. But in Newton he lingers longer and captures well the loneliness and sorrow that can affect a man who stands alone, obsessed with “vague guilts and vaguer doubts” and with no real confessor in his midst. His decline almost feels inevitable and with the ongoing questioning of himself (“…was it merely that a man surrounded by animals long enough became more of an animal than he should?”) Tevis achieves an agreeable balance of depth alongside pacier sections.

Toward the end of the book there is a mention of the Watergate scandal that, for a book written in 1963 is remarkably prescient, and would hint at Tevis having made later amendments to his work. The pictured edition doesn’t make mention of this and one wonders what other changes may have been made to the original text. But original text or updated probably doesn’t matter for The Man Who Fell To Earth is a satisfying tale that contains a wholly science-fiction premise but delivers it lightly with little emphasis on the science and much more on the fiction.

Thanks for this, Stewart. I really like the film version, and it hadn’t occurred to me to check out the book. I am particularly interested in the book-to-film conversion, so I will have to get a copy of this.

Is it better than the movie? I didn’t quite get the movie, but I was very young when I saw it.

I wouldn’t know, sorry, as I haven’t seen the film. I hear it’s quite impressionistic though, which the book is not.

Hey Stewart happy new year! Please send me your postal address as I want to send you a book.

I hope you’re well!

Jennifer Clement

Happy New Year, Jennifer. I’ve sent you an email.

FWIW (and it’s close) I’m inclined to think that Mockingbird (also by Tevis, natch!) is a slightly better book.

It is, probably, more overtly SF than TMWFTE, but has a similarly introspective tone (although it features robots, it’s about human self-discovery…like Newton in the other novel). All that said, I’m not sure that Tevis was ever a great novelist (in any genre), but that’s by the by…a very good second-string piece of fiction.

Is it really better than the movie? I didn’t quite get the movie, but I was young when I saw it.