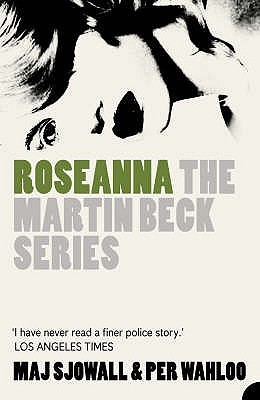

“Most crimes are a mystery in the beginning,” says the Public Prosecutor in concluding a press conference discussing a woman’s murder. In this case, it’s a real mystery: a woman’s naked body has been accidentally dredged up from a Swedish canal and, with no clues forthcoming and nobody reported missing in the area, the police can’t even put a name to the victim. This is the gambit of Roseanna (1965), the first of ten police procedurals featuring Martin Beck, written by husband and wife team, Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall.

Where much of the crime fiction that I’ve read before – few, admittedly – has focused on the methods of the lone detective, from Holmes to Poirot, it was a refreshing experience to find that Sjöwall and Wahlöö had situated their crime story away from supersleuth glamour and into the realistic drudgery of the Homicide Bureau where being First Detective Inspector is just a job like any other, albeit one that requires a certain dogged mindset.

As jobs go, Martin Beck’s is one that appears to be led by some glimmer of predestination —

Martin Beck wasn’t chief of Homicide Squad and had no such ambitions. Sometimes he doubted if he would ever make superintendent although the only things that could actually stand in his way were death or some very serious error in his duties.

— and, as seems the staple for any dour detective, once it gets its hooks into you, all else falls by the wayside, notably the marriage, which had “slipped into a fairly dull routine” and, in snippets throughout, shows little chance of reparation:

At five-thirty he called home.

‘Shall we wait for dinner?’

‘No, go ahead and eat.’

‘Will you be late?’

‘I don’t know. It’s possible.’

‘You haven’t seen the children for ages.’

Without doubt he had both seen and heard them less than nine hours ago, but she knew that just as well as he did.

‘Martin?’

‘Yes.’

‘You don’t sound well. Is it anything special?’

‘No, not at all. We have a lot to do’

‘Is that all?’

‘Yes, of course.’

Now she sounded like herself again. The moment had passed. A few of her standard phrases and the discussion was over. He held the receiver to his ear and heard the click when she put hers down. A click, and empty silence and it was as if she were a thousand miles away. Years had passed since they had really talked.

Where Beck’s head is really at is in the thrill of the case. However, when the victim surfaces in early July the investigation moves at a pace typically reserved for snails. The aforementioned press conference is bereft of details because the case itself has few leads. Even when a tip off from Interpol finally kickstarts proceedings, the pace of the case still seems lethargic for the contemporary reader, yet in no way releasing its grip.

In this age of mobile telephones, computers, email, and electronic records, it almost seems incredulous the way Martin Beck and his colleagues go about their days: waiting for files being sent through the post; hunting payphones to report back information; travelling back and forth between Stockholm and the town of Motala; scanning manifests for data that, today, would only be the click of a button away. And when things start moving, tracing the crime to a tourist-filled boat, the scope of the case becomes apparent:

Eighty-five people, one of whom was presumably guilty, and the rest whom were possible witnesses, each had their small pieces that might fit into the great jig-saw puzzle. Eighty-five people, spread over four different continents. Just to locate them was a Herculean task. He didn’t dare think about the process of getting testimony from all of them and collecting the reports and going through them.

There are no clues in Roseanna conveniently left to help solve the crime. What’s required here is old-fashioned police work, following defined procedures, to whittle that list of eighty-five down to a single murderer. The cops read over case notes countless times; they scour testimonies again and again; each time they hope to spot something between the lines that they haven’t seen before. The problem they have is that in real life people are not so much black or white as they are shades of grey and so justice comes to face the obstruction of ulterior motives and withheld confessions. This quality of people is something of which Beck is conscious, as shown in one particularly wooden moment, where he separates himself from the media sensationalists that cover such stories:

Martin Beck straightened up. ‘Remember that you have three of the most important virtues a policeman can have,’ he thought. ‘You are stubborn and logical, and completely calm. You don’t allow yourself to lose your composure and you act only professionally on a case, whatever it is. Words like repulsive, horrible, and bestial belong in the newspapers, not in your thinking. A murderer is a regular human being, only more unfortunate and maladjusted.’

When Wahlöö and Sjöwall wrote their Beck novels they took on alternate chapters. Any inconsistency of style is perhaps ironed out by translation, but the prose here, spare and taut, is little more than functional, yet it also reflects those policeman’s virtues: calm and logical and stubborn. There are times when dialogue feels stilted but it’s a minor deflection from the narrative that is almost, from start to finish, gripping in its way without, given that it was translated over forty years ago, feeling dated.

Although the first of ten novels, the expectation was that they would be taken as a single, larger arc called The Story Of A Crime. Of the crime in Roseanna, I’ve barely mentioned it as that would detract from the experience of rolling up the sleeves and following the logical progression of Martin Beck and his team as the day job becomes an obsession —

Martin Beck remained and listened to the work day die away. The telephones were the first to become silent, then the typewriters, and the sound of voices stopped until finally even the footsteps in the corridors could no longer be heard.

— and the seemingly impossible case has its story unravelled and the resulting thread leads from eighty-five suspects to one. Most crimes may be a mystery in the beginning, but they can be measured in the satisfaction of their conclusion. And, so, with this one case satisfying, it’s a pat on the back and back to the day job: there’s nine more cases to be solved.

I own a copy of this, but haven’t read it yet. It sounds like it would make a good read between weirder or more literary stuff. Something to cleanse the palate and refresh.

Also, it sounds quite fun, though fun perhaps isn’t exactly the right word…

Good to have you back by the way!

Max, it’s good to be back. I’d say that, yes, they are nice little palate cleansers. Quick reads, too. I’m coming to the end of the third novel and, I’ll certainly talk about this more with subsequent reviews, but it’s interesting to see the characters develop across the stories already. And the variety of the crimes, from book to book, stops it from becoming formulaic.

I ve not read martin beck only nordic crime read is jo nesbo ,sounds ok not huge crime fan but as you say they tend to be quick reads stewart ,know janette (bookrambler) fan of this series ,all best and welcome back stu

I’d be interested to see follow-up reviews. Half the pleasure of these sorts of series is watching the development of the characters. If that works well, it makes the whole thing much more tempting.

The climax of the book was heart pounding, particularly the waiting part.

I liked the bit where they interviewed the people on the boat but disregarded people who would not make good witnesses “children and old women”. They obviously have never met Miss Marple!