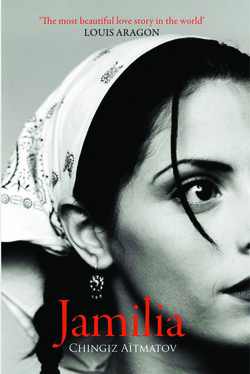

When I first read Jamilia (1957, tr: James Riordan, 2007) by the Kyrgyz writer, Chingiz Aïtmatov, I could never square it with the Louis Aragon quote adorning the cover, declaring it “The most beautiful love story in the world”. With hindsight, in rereading, I suspect it was the limitations of the word ‘love’. I remember being taught that ancient Greek had several words for love, each with specific meanings, and that many other languages do too. Therefore, this book is a bubbling kazan of such varieties.

There’s love for nature; for art; familial love; and the love of friends, not to forget the traditional young love essential to many a coming-of-age tale. Our narrator is Seit, reflecting on when he was fifteen and young still to be fighting at the front, like his brother. While the war rages on, under the Soviet collectivist model, farming has been delegated to the women and children.

An artist now, it’s one of his own paintings that triggers his recollection of Jamilia, his brother’s wife. Brash but respected, it’s expected she will one day play matriarch to the village, just as Seit’s mother does, provided she remains loyal to God and her husband. But as letters from the front arrive, with a roll call of addressees, firstly to “my dearly beloved, esteemed father”, and then the family, enquiring on their health, before ending with the brutal “and give my regards to my wife”, it’s clearly not a marriage bound by love.

But love is in the air as, to their remote village, somewhere near the Kazakh border, a wounded soldier comes. And Aïtmatov shows himself a keen observer of people, giving us the gradual changes in temperament and emotion as Jamilia finds love. But also as Seit discovers what it means to love, in all its guises, which tests him when his brother returns from the war.

If the novel is sparse and peopled with few characters, then it reflects its setting, an empty, mountainous world on the edge of vast steppes at the far end of Soviet reach, where life is hard and nature abounds. Barring a few geographical signposts it has the air of myth, bringing its small drama of far flung places into the realms of the universal and showing the power of art