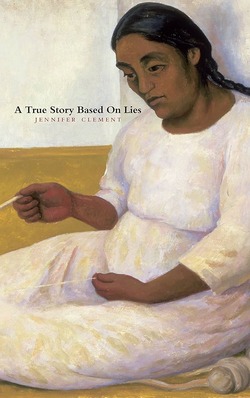

Women are at the heart of Jennifer Clement’s 2001 fiction debut, A True Story Based on Lies, which looks at the upstairs downstairs dynamics in wealthy Mexico City. Our gateway to this world is Leonora, a young villager sent for a convent education so that she may exceed her mother’s career of collecting twigs to make brooms. From there she’s taken into the employ of the O’Connors, to tend the house and look after their children.

Clement is first and foremost a poet, and she brings this to bear in her dual narratives that spill light and lyrical on the page. First of these is a third-person account centred on Leonora, and her relationships with the household, the old maids and the increasingly distant Lourdes. The other narrative comes from Aura Olivia, known as Fly, the O’Connor’s daughter, though unbeknown to her she’s really Leonora’s child with Mr O’Connor. Where there’s an unspoken bond between the two there’s clearly a separate affection.

In the confines of the O’Connor household, we are witness to the classism against Mexico’s indigenous people in the way Leonora’s life is controlled not just by her employers, but also the religious infrastructure that make her available for exploitation. But in the form of Mr O’Connor we see a patriarch exercising his will on all, overriding his wife, and enjoying his many infidelities without repercussion.

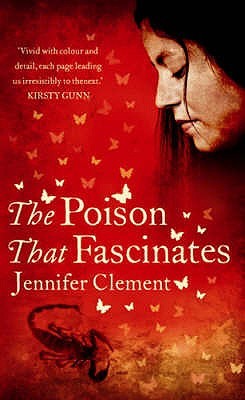

There’s much at play here, in what is, thanks to Clement’s breezy, isolated paragraphs, a short book with much to say. The derision of customs over the Christian teachings sees the staff conflict with the family, if somewhat toe the line. But there’s clearly depression, power struggles, and internalised misogyny too. In one instance involving the law, the equality of the poor against the wealthy is cast in doubt. And there’s a few threads, briefly mentioned, that perhaps hint at an interest that would prominently manifest itself in Clement’s 2008 novel, The Poison that Fascinates.

At no point does the narrative seem contrived, with every event flowing with logic and sad inevitability. Though an interesting, if ultimately unsuccessful, denouement that revisits Leonara’s narrative as a purely mental journey looks to tie up the book before a final gut punch takes the book to a dark form of sorority. Every leaf is a mouth, as one narrative states, which seems to relate to the number of stories that can be told about a tree. With the title, if Mexico is the tree, then this story is a single leaf, and, although a work of fiction, the story that mouth tells is true.