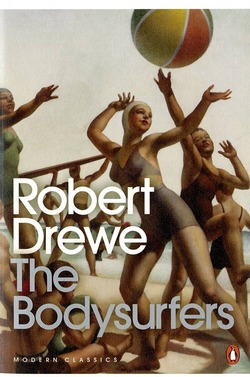

Three generations of the Lang family take up many of the stories in Robert Drewe’s The Bodysurfers (1983), a work that leans in on the men, their faltering relationships, and the perennial comfort of the Australian coast. It’s a place of sex, surf and sharks; a place where so much happens so as to seem inseparable from life itself.

In the opening story, The Manageress and the Mirage, the themes are quickly set as Rex Lang takes his children out for a Christmas meal at a hotel. The narrator, his son, Max, notices the manageress informally calling his father by name. And when she pulls out presents for them, it becomes clear that he’s introducing his new partner to his kids. These kids – Max, Annie and David – are visited again, across their lives in the following stories. Like their father’s situation, their own doomed relationships, coming and going like the tide, form the focus of many. David’s Lang’s lovelife, especially, sees different partners from tale to tale.

The only story set outside Australia (Looking for Malibu) sees David in California, where he observes that “when Australians run away they always run to the coast. They can’t help it.”, which is certainly thematic of the collection. The beaches that provide these stories are there for the escapes they provide, whether that be for crimes (Shark Logic), infidelities (Baby Oil), or, as in the title story, a break from domestic living.

While the stories mostly come at the Langs from different angles the family is not always the focus. In The Silver Medallist, we look back at their mother’s original fiance, an Olympian who, it turns out, had a dark secret that was eventually exposed. After Noumea revisits a side character from an earlier story, exploring how he’s coping following the end of another doomed relationship.

Drewe’s writing is wonderfully varied, shifting tonally to each story’s needs; at one moment poetic, another matter-of-fact; at home in third person as he is in first. The View from the Sandhills may cause some to roll their eyes, with its sexual and outdated language, as it invites us to inhabit an ex-con’s story. Clearly unable to form bonds, and perving from a safe spot on a beach, it’s an increasingly sinister piece that is only tangentially related to the Langs, primarily Anne. But it’s well ventriloquised and embodies the character absolutely.

If that story touches on the Langs, there are others that seemingly bear no relation, such as The Last Explorer, which turns its gaze inland from the beach. It’s an oddly different piece from all the others, while staying on theme, but its historical account and unnamed character leave a certain vagueness. That said, many of the stories have a certain ambiguity to them, but one can never feel that it is anything other than controlled restraint and that the clues, if not directly referenced, are there, implicit in the text.

Given the disparate nature of the stories, the range of characters and the various times they inhabit, there’s much to reread here, drawing lines between them. If anything, the beaches that provide Drewe’s stories are the only unchanging things in a world where the characters’ lives are in flux. They are a sunny, sandy asylum for a maddeningly complex world, and it’s no wonder the people retreat there given how much events seem to pour down on them.