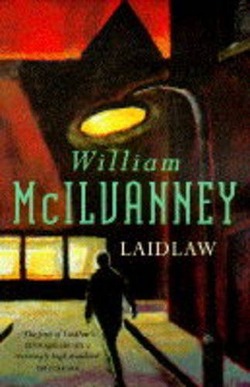

Love or hate the term, William McIlvanney became the father of ‘Tartan Noir’ after his fourth novel, Laidlaw (1977). Many of today’s Scottish crime writers, like Ian Rankin, cite its influence. Although now considered a crime classic, one has to wonder whether McIlvanney intended to pen such a book. Sure, the title takes its name from the detective at its centre, but the mystery at the novel’s heart is far greater, more philosophical, than others of its day.

Jack Laidlaw is something of an old school detective, a hard-boiled guy in a world of procedures. Assigned a partner in Harkness, Laidlaw leads this wet-behind-the-ears protege through Glasgow’s gritty underworld – a place of old pubs, gangs, and gambling – on the trail of a murderer following the discovery of a young girl’s body in a park. Though we know the killer from the start, the thrill comes from knowing there are other factions also hunting him, all getting closer with each discovery or betrayal.

Being my first McIllvanney the biggest surprise is that his prose is a gem; poetic, contemplative, and shot through with the dark with that capure’s the city’s humour. Each page sparkles with one line or other that I’ve never really got from other locally-set crime novels. The city feels alive in his hands.

To me, the book shows three Glasgows: one I know, one I knew, and one from before my time. The landmarks have stood throughout, attitudes have moved to the fringes, and the society is recognisable yet somewhat askew from the contemporary. But it’s a deeply Glaswegian novel, from scrutiny of the city’s social and religious ills, through to the dialect as written down. It may be going on fifty years, but it shows little of its age.

Reaching beyond the parochial, its existential streak elevates it to a more universal appeal. McIllvanney was once dubbed ‘the Scottish Camus’, and it’s definitely here in its questioning characters as they search for meaning. That the crime at the heart of the book happened is neither here nor there; the reasoning is far more inscrutable. Laidlaw seeks not to follow media outrage with headlines that shriek about monsters, but recognises that there are no monsters. Just men.