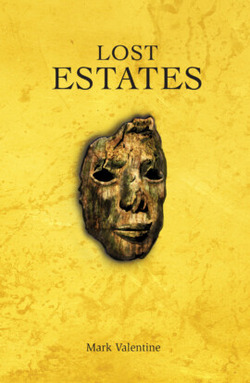

Mark Valentine’s collection of short stories, Lost Estates (2024) is bookended by two long tales that begin with journeys through an England abundant in history and arcana and ultimately end in the supernatural. A Chess Game at Michaelmas, is a strong opener, and invites us to a dilapidated mansion as its narrator explores local variants on historical peppercorn rents, with the unusual ancient arrangement on this mansion, collected during the visit.

The niche interest here is exemplary of Valentine’s narrators. They are antiquarian in their motivations, and the stories see them single-mindedly in pursuit of lost works, personal superstitions, or picking at the history of English inn signs. Indeed, in the latter (The Understanding of the Signs) what begins as an exploration of said signs soon slips beyond the veneer of reality to find a deeper resonance, where both ‘understanding’ and ‘signs’ find new light.

The borders of reality, as per the influence of Arthur Machen, are where Valentine pitches his tales. The House of Flame, is a title not unlike Machen’s more famous works, and indeed it’s a biographical take on the Welsh mystic, imagining, by way of the death of General Gordon (a somewhat forgotten example of British derring-do), how the young writer finds inspiration that drives his burgeoning development as a writer. Another writer, in The End of Alpha Street, seeks to collect personal folklores, those unusual superstitions that people make for themselves.

There are other interesting tales, such as The Seventh Card, where a man attempts to identify the mysterious sender of Christmas cards and a personal favourite in And maybe the parakeet was correct, where a journalist contrives to deliver copy on human interest stories with tangential nods to football and, along the way, experiences an uncanny encounter in the streets of Paris. Laughter Ever After may help certain bookish collectors feel seen with its lighthearted trip to a village in search of an obscure ghost story that may not exist.

While time feels suggested in these stories, rather than observed, place is very much to the fore. A couple of stories take place in urban areas, but the book’s comfort zone is clearly rural, among villages and the lonelier spots at the corner of civilisation’s eye. Fortunes Told: Fresh Samphire, is Valentine’s prose at its most ethereal as one man investigates the disappearance of a man called Crabbe, who may – or may not – be the Philip Crabbe that appears in the later story, The Readers of the Sands, where a trio of experts are invited to his house to determine whether there are hidden messages in the sand on the nearby beach. Closer, The Fifth Moon, also takes us to sandy spaces in search of King John’s lost treasure, and discusses theories and posits its own.

Though the stories never reveal their full hand, they do satisfy and offer much to mull over and reward rereading, thanks to how lightly they wear their erudition. Certainly there is much allusion that, having chosen to explore these threads, the stories gain depth. That the supernatural elements and new worlds barely glimpsed offer little clue as to whether their spectral nature is benign or has hostile intent. But even when things seem more explicit, such as in Worse Things Than Serpents, we are never truly sure. There, the narrator finds, off the beaten track, a mysterious untended bookshop that offers only books about serpents, one of which, ignorant of the price he deems to purchase.

Title story, Lost Estates, with its intimation of ungraspable worlds beyond our own feels a fitting choice for the collection’s title as the stories’ numinous qualities hint at, while never truly revealing, alternative planes. Each story feels rich in historical detail and suggestions of the supernatural and, within their ambiguity, there is much to enchant and contemplate.