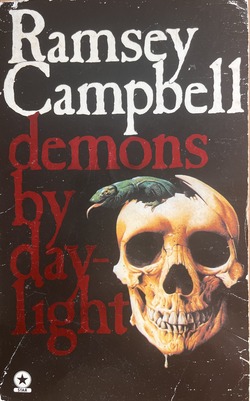

Demons by Daylight (1973) was Ramsey Campbell’s second collection of short stories, following on from The Inhabitant of the Lake and Less Welcome Tenants (1964). Truth be told, I’ve never really got on with that debut; it’s cod-Lovecraftian prose puts me off. That said, it was an achievement for a sixteen year old. This second book is a different prospect, having discovered Vladimir Nabokov and Graham Greene, the still young Campbell changed his style wholesale.

The stories are split across both Campbell’s Liverpool, where psychological horrors abound and Brichester, the city at the heart of his take on Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. Opening story, Potential, is firmly lodged in 1960s counter-culture, where a young man walks into a hippy gathering, and is befriended by another attendee who suggests another place that may be more to his liking. What begins innocently enough leads to horror of cosmic proportions. That it opens the collection suggests Campbell is flag-planting his territory with this new approach: the Lovecraftian influence remains, but the delivery is going to be different.

So different, in fact, that Campbell finds space among the stories for some meta-fiction, with The Franklyn Paragraphs, an enjoyable romp – and spin on the Lovecraftian mythos – with the author himself on the trail of missing novelist, Errol Undercliffe. The Interloper, a story purportedly by Undercliffe also appears. Lovecraft isn’t the only model as The End of a Summer’s Day, one of the collection’s standouts for me, brings Robert Aickman to mind. A short tale about a newly-wed couple on their honeymoon taking an excursion to a cave. It pulls the rug out from under the couple, with no explanation. Where the ending seems slightly innocuous, it gains from a further reading, where a throwaway line midway suggests a greater tragedy to come.

Such subtlety is part of Campbell’s trademark here; he’s not the type to hold readers’ hands in the dark. His narratives require patient ingestion and invite cross-referencing of details. The spaces between the narratives require their own level of consideration. With each reread they open up without ever fully revealing their hand. Campbell is so in tune with his characters’ psychological states that we are often never even sure if the horrors are real or tricks of the mind. With abrupt time jumps between paragraphs even linear narratives feel disorienting. Add to this particularly off-kilter perceptions, such as a bus “swallowing its queue” or, when a man wanders among trees (“branches wept on him”), and we have a constant sense of unease.

Some stories, despite reading them several times, are sadly baffling; too abstruse as to be fully satisfying. However, Concussion, a lengthy fantasy where an elderly man and a young woman on a bus have a week-long fling in the past is a gem that rewards multiple reads. It’s a sustained fever dream, flitting in and out of reality, memories, and other influences so that we are never truly grounded in what may be going on.

Though there are killers and ghosts, and even a take on garden gnomes in Made in Goatswood, nothing feels conventional. The Enchanted Fruit luxuriates in nature writing as a man takes from an unusual tree with consequences. The Sentinels looks to standing stone lore, and The Stocking is a grounded and nasty tale of office flirting, though its reference in The Franklyn Paragraphs arguably pulls it into Campbell’s wider mythos.

The most unusual thing about Demons by Daylight is how long, for a book less than two hundred pages, it took me to read. I found myself reading the stories over and over, searching for the key detail that would unlock the tale. Campbell’s stories feel dense, thanks to layers of detail and references, mostly literary and cinematic, but they do reward patience, mostly. Yes, the collection feels uneven, but this book is a young writer finding his new style. This year he’ll have been publishing books for sixty years, so it’s clearly served him well.