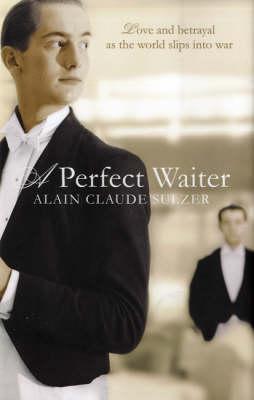

The role of a waiter is to perform unseen, to serve people and, barring the occasional nod or small talk, to be both discrete and unmemorable. They must give nothing of themselves away while attending to those they assist. One who exemplifies this can be the perfect waiter of the title in Alain Claude Sulzer’s novel, A Perfect Waiter (2004, tr: John Brownjohn, 2008). In this instance, it’s Erneste, the embodiment of order and restraint, in both his professional and private lives.

Set in both 1930s and 1960s Switzerland, at a grand hotel, the book sees its later period shattered by the arrival of a letter from America harking back to the earlier time. The letter is from Jakob, a German man whom Erneste had, when they were in their early twenties, trained, shared a room with, and experienced his only true love. This at a time where the consequences of their relationship would have been disastrous.

But what is love for one person is but an indulgence for another as a sort of love triangle develops with the arrival of a well-to-do guest. Julius Klinger is a writer of great repute, tipped for the Nobel, and effectively a veiled Thomas Mann, who made a similar exodus with his family to Switzerland and then to America, escaping the increasingly perilous nature over the border in the Third Reich. Erneste’s life is shattered when he catches them in flagrante delicto.

As the titular waiter, Erneste embodies the many themes that swirl around in the novel’s two periods. By making himself vacant to those he serves, we see the effects of loneliness and keeping one’s identity hidden away. At a time where his homosexuality would be harshly condemned, his professional invisibility becomes a sad mirror of his own shattered hopes for sexual liberation. But with the addition of Klinger, the flirtation of class and power compound Erneste’s quiet agony as his lover’s attention shifts upward rather than remaining with his equal.

Sulzer’s prose is calm and meticulous, like his waiter, expertly guiding us back and forward between the two crucial decades. Though the narrator is omniscient, there’s something of the reserve and repression of Ishiguro’s Stevens (The Remains of the Day, 1989). It has plenty of memorable set pieces, such as the Erneste’s voyeuristic approach to Jakob being measured for his uniform or their first sexual encounter. But also more grim moments as queer-bashers exercise vigilantism and one character takes their life.

With the Mann-like figure of Klinger, and his interest in Jakob’s handsome youth, it’s easy to view him, in reference to Mann’s Death in Venice (1912), as a Tadzio, the object of infatuation for a writer and the unspoken passion of Erneste. At the start of the book, when Jakob’s letter arrives, Sulzer gives us this passage:

“The past was locked away in his abundant recollections of Jakob like something inside a dark closet. The past was precious, but the closet remained unopened.”

That Erneste is unable to leave his past, or be himself is the novel’s core tragedy in a book replete with them. The journey from idealistic and professional twenty-something to middle-aged standard-bearer of lost time and regret is complete. But the perfect waiter handles this by remaining invisible, a shadow passing through life, serving the world unnoticed, and the importance of being Erneste is quietly lost.