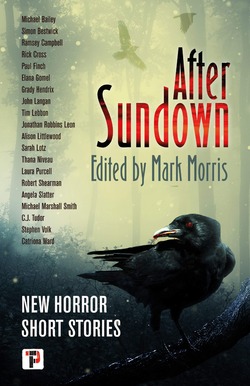

After Sundown (2020) is the first from an annual non-themed horror anthology by Flame Tree Press. With no particular focus, editor Mark Morris has cast the definition of horror wide, ensuring that the stories presented offer a real mix. Sixteen of the twenty stories were commissioned by well-kent names in the field, meaning the remaining entries were from open submissions, though the four are not identified.

As openers go, C.J. Tudor’s Butterfly Island is a high-octane thriller in miniature. It brings a boatload of characters onto a mysterious tropical island and involves so many plot points in its seventeen pages that it’s hard not to feel like it’s the trimmings from some larger work. With bountiful sarcasm and comic stylings (“Kaboom!”) it never really won me over, but it at least set me up to be wrong-footed by the contributions that followed.

Tim Lebbon’s Research raised a smile by exploring the familiar idea that horror writers are nice because they expunge their darkness on the page. Here a writer is kidnapped and, prevented from writing, observed to see what happens. Another writer, in Ramsey Campbell’s assured Wherever You Look, discovers at a reading that his canon shows signs of being influenced by a short story he read as a child and no longer recalls. This sends him on a mission to read it once more and exorcise its influence, but its psychological effect drags him deeper into darker places. Allusive and perhaps somewhat autobiographical, it’s ultimately unsettling.

If Campbell’s story feels vague to some, then Catriona Ward’s A Hotel In Germany may be lost to many. It’s a deliciously odd study of love and servitude told through the relationship of Cara and ‘the movie star’. The ambiguity of Cara – petlike, sentient, obedient, and almost ageless – brings a whole layer of mystery to this seemingly symbiotic couple, and the world beyond the hotel, fleetingly glimpsed – is tantalisingly speculative. Similarly, Alison Littlewood’s Swanskin is another story wonderfully enclosed in its mythology. A slow-burn exploration of gender roles in a fishing village, it’s a spin on the swan maiden folklore that slips off its feather robe for a ghastly conclusion.

Being horror, such endings are often anticipated. Simon Bestwick’s We All Come Home, a tale of one man returning to his childhood trauma, is a solid piece of writing though its conclusion has a sense of having seen it all before. The Mirror House by Jonathan Robbins Leon, the story of an unhappy marriage as a woman realises she’s a box-ticking exercise to her older husband is suitably creepy though its ending feels predictable. Ditto Murder Board by Grady Hendrix. Farcical and familiar, here a Ouija board leads to disaster when a message, interpreted in one way, is more ambiguous. It’s a pacy piece of plotting, but also surface-level stuff and rather forgettable.

Any anthology is bound to contain some run-of-the-mill stories like that (admittedly, it’s all personal taste) and After Sundown is no exception. That’s the Spirit by Sarah Lotz is one such tale; the story of a fraudulent medium who may be regaining powers. It’s nicely character-driven but fairly conventional and, if it surprises, then it will only once. Thana Niveau’s Bokeh has a child acting strange with imaginary friends while processing her parents’ split. I thought its unusual representation of the fae in the shapeless unfocused regions of a photograph was great but overall it’s not a particularly interesting story.

But where some stories don’t deliver, others come out swinging. In The Importance of Oral Hygiene, Robert Shearman has one woman writing to another to warn her about the dentist she’s visiting. It’s a fun, tight, and grotesque piece of body horror set in the 19th century featuring a debauched indulgence in nitrous oxide. Stephen Volk’s The Naughty Step is a bleaker affair as a social worker arrives at a crime scene to help escort a young boy, banished to the titular step before witnessing his mother’s murder, and unwilling to leave without her permission. It’s devastating stuff, well-observed, and its characterisation oozes frustration, compassion, and trauma. More domestic horror is found in Michael Marshall Smith’s It Doesn’t Feel Right, which grows out of the most mundane of situations: a man getting his child ready for school each day and the kid fighting back at having to wear uncomfortable socks.

If socks don’t feel right, then I felt the same way about Laura Purcell’s use of a journal in Creeping Ivy to deliver the story. It’s a gothic story with its dilapidated manor, dead wife, uncanny botanics, and hints of madness. The entries just read like a regular narrative, despite an opening gambit that observes they supposedly get more scrawled as they go on, though those scribblings do produce a nice conclusion. Rick Cross, in his Last Rites for the Fourth World, opts for ending where he began in this matryoshka of a story, like a Cloud Atlas in miniature. Environmental in theme, I found it rather dull in its imagining an end to the current crop of folkloric entities. Similarly speculative, and with a more ambiguous apocalypse, was Michael Bailey’s Gave, which jumps back through the key moments of one man’s life as he gives blood to save humanity. It flows nicely but doesn’t provide much of a chill.

If giving blood voluntarily is horrific, then spare a thought for the cast of Lewis Carrol’s Wonderland in the sanguine pages of John Langan’s Alice’s Rebellion which opens with many of their heads on sticks. It’s an overtly political piece, a dark fantasy that imagines Tweedledee and Tweedledum having found power in our world. The blatant comparisons to two tousled-hair blonde leaders of the day feel, even just a few years later, dated. Its central theme is more universal in questioning revolutions, their martyrs, and who will rise from such sacrifices to make the world sensible again. But for some, such as the ghost in Angela Slatter’s Same Time Next Year, the world she haunts can never be sensible as its memory comes to her in incompatible fragments. Like her, we never really get to see her life in full, and can only speculate with the hints given, making it a nicely paced tale with room for reflection.

There’s reflection too in Mine Seven by Elena Gomel, as a woman comes to terms with her roots. But this is also an enjoyable creature feature, touching on climate change and natural resources, set in the icy desolation of Svalbard. It’s well done, in plot and pace. That the monster stalking the island comes from Chukchi folklore makes it an interesting and educational experience.

Boys of a certain age in 1970s Britain are likely to have had a different sort of educational experience when ‘mucky mags’ were passed around like currency. This rite of passage forms the backbone of Paul Finch’s Branch Line, which is half a coming-of-age tale and equally a ghost story. Delivered like an interview, recalling the time when one boy went missing, the interviewee tells his side of the story about his relationship with his old companion as they walked, Stand By Me style, along a railway line in north-west England. It’s a nostalgic piece and captures a somewhat lost era. And its ending is a fitting way to end not just the story but also this fun and varied collection.